We found ourselves arguing with a map vendor over the price we had agreed upon for her map. She had

agreed to sell it for Y2 (US$.25), but later tried to demand Y3 (US$.37). I started to walk away and she

stopped her arguments with a mischievous grin. Then she complained about the condition of one of the bills

we gave her. Sometimes it's difficult to try and adapt to an environment and still be rational!

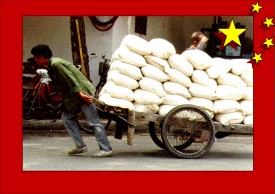

There is an enormous range in levels of prosperity from one person to the next and from one neighborhood to

the next in Socialist China. In the train stations you can see whole farm families with a few small bags

that were certainly all their worldly possessions as they look to migrate to the city. One dirty farm boy

from Jiangsu Province was so excited to see a "long nose" that he just had to hug me a couple of times

before dancing with excitement. We saw a man pushing a cart which had a tree trunk. This was no

ordinary small  at least twenty feet long and three feet in diameter. At the other end of the spectrum are the

more affluent Chinese women dress in sexily-short skirts that would make them look at home among

the more affluent of many of the world's major cities. Then there are the Jeep Cherokees (we

saw six of these parked in one block in Beijing) and Audis being driven past tens of people

who can't afford more than a Chinese-made bicycle.

at least twenty feet long and three feet in diameter. At the other end of the spectrum are the

more affluent Chinese women dress in sexily-short skirts that would make them look at home among

the more affluent of many of the world's major cities. Then there are the Jeep Cherokees (we

saw six of these parked in one block in Beijing) and Audis being driven past tens of people

who can't afford more than a Chinese-made bicycle.

Some older, crowded neighborhoods that were accessed by alleyways were flooded after a day's

rain. In sharp contrast to these "ancient neighborhoods" were sky-rises and international-quality

shop lined streets. One of these old neighborhoods, called a hutong, had been leveled

and the area served as a buffer zone separating more hutongs from the already standing

sky-rises. Many of the sky-rises had large stylized golden Chinese characters to identifying

them rather than Western names or even the Romanization for the Chinese names.

contemporary work in the old Forbidden City

contemporary work in the old Forbidden City

In Beijing, west of the old Forbidden City and Zhongshan Park is Zhongnanhai, the former residence of Chairman Mao Zedong and now the residence of China's current political elite. Zhongnanhai also seems to spill over into a strip of land between Beihai Park and Jingshan Park. On the western side of the red-walled new Forbidden City is a hutong community, which not unlike other hutongs in Beijing is old, dilapidated, dirty and crowded, giving one the impression like that of the White House being across the street from a ghetto like Harlem, less the fear of crime, at its worst. Going south from the walled complex that bears the same color as the former emperors' residence there is also what appears to be army barracks should the important residents ever fear the wrath of their "constituents".

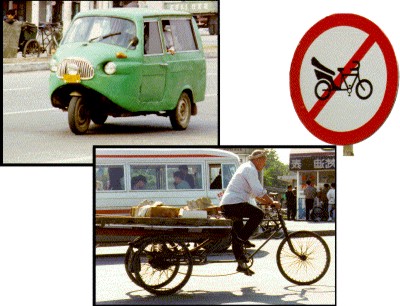

I measure the extent of industrial development in China by the amount of smoke stacks pumping various shades of gray-to-black and orangeish smoke into the air. The heavy reliance in China on coal is visible in the sky, in the numerous three-wheel bicycles and carts laden with the cylindrical blocks led by young men still strong enough to pull such a load; and in the common sight at the entrance to a hutong of a fresh stack of these coal blocks are piled high (note that this picture was apparently taken just before a new delivery!).

One of the first things a waiguo ren (foreigner) is bound to notice when walking through a Chinese street is that there are vast sums more adults riding bicycles than there are riding either motorized bicycles, motorcycles, or cars. The question that comes to mind is "how much more development can China sustain?" What would China's already unhealthy air be like if those riding bikes today got into cars tomorrow? Trash is another problem in China that is growing proportionately with development because as Chinese consumers purchase more non-biodegradable goods and goods in non-biodegradable packaging, these and related items are tossed into the streets and rivers.

Walking through Shanghai's main train station, Karen noticed the Chinese equivalent of those cigarette extinguishing/trash cans topped with sand that are popular in American hotels. In the more simple Chinese fashion, there was a large metal bowl nearly filled with water that had gobs of spit and extinguished cigarette butts floating on top. Using the bathroom at the train station was fascinating from a voyeuristic standpoint, unfortunately I was one of its patrons as well. The foyer as it were led me to wonder if it wasn't like the old opium dens but in this case the wild intoxicant of old was replaced by a milder intoxicant, nicotine, whose use was prohibited elsewhere in the terminus. This is were the wash basins for both the women and men are located and the bathrooms are entered only after passing through this area. A seated man and a seated woman collected the admittance fee at the respective bathroom door where after entering you can't help but wonder if a high concentration of methane gas and ammonia could kill a man. Each stall is a cube about 4'x4'x4' and I uncomfortably towered above the rest of the men as I was not used to squatting when urinating which is done into a ditch that runs along the floor roughly through the center of the cubed stalls which are on either side of the room. Public bathrooms are fairly common in Shanghai and Nanjing but laying in the ditches are often the colorful variety left behind by previous visitors because the ditches, which are flushed manually, are flushed infrequently (I couldn't help but remember a Japanese story from the 1920's where in it was revealed that excrement of city residents was prized by the farmers as nutrient for their crops and wonder if these ditches were not really "flushed" at all). Residents of the poorer neighborhoods in the cities we visited use ornate chamber pots that I saw one man dump into a small manhole-like covered sewer that was perhaps twelve inches in diameter. Judging from the stench that filled the air for a few minutes afterwards it was used exclusively for dumping chamber pots. A few feet away was the small, walled-in neighborhood garbage dump which was merely an extension to the rest of the neighborhood dwellings though it was located on a corner.

Small Chinese children generally have slits in the crotch of their pants so they can defecate anywhere without the parents having to worry about the chore of cleaning or changing diapers as is the case in most other places. The only thing as bad as letting children defecate just about anywhere would be the parents spreading the problem by attempting to clean the waste in a land that has no facilities for doing such a thing and has nearly equally inadequate waste disposal. It was one thing when, as a child, I had seen a small boy stand at a street corner and urinate into the street; it was quite another when in Zhengjiang I saw a girl, perhaps five-years old squatting near a curb with her ass pointing towards store fronts expelling large quantities of excrement while a few feet away there were two young women who were picking up vegetables off the sidewalk to wash them(had the girl been taught the benefits of turning the other way, she would have at least been defecating into the gutter of the street).

Given the bathroom situation and the general drainage problem in China's cities and countryside, it is surprising that there aren't more health concerns in the country where meat is delivered uncovered on the backs of bike carts, and butchered on tables in the open-air just off the streets. Many of the foods are prepared just off the street and left uncovered awaiting consumers.

In addition to these policy-making concerns for China's future leaders there is the cultural problem of personal hygiene. Personal hygiene in China is the worst we have seen in any country we have visited, including the one country that had a very similar trash problem, the Philippines. Spitting appeared to be a national pastime for Chinese men and women alike despite government efforts to reduce its incidence with bilingual signs in tourist areas.

In Tai'an we ate at a restaurant where we were given cups to drink tea from that were sticky with dirt. A smarter person than myself would have left the restaurant the minute a man working at the restaurant approached us to either take our order or check the order we gave to someone else because he was absolutely filthy. We were praying that he wasn't going to be involved in the preparation of our food, but it was bad enough that he delivered it when it was ready. In the same town, we purchased a small bag of rolls and the bag was sticky with filth.

As we sat in one restaurant, I noticed how a woman was littering the floor at the side of her table with ashes from her cigarette. Then Karen pointed out that a restaurant worker swept the floor after the patrons left their table because there was so much garbage, like the bone from a piece of chicken that one woman had spit out, left on the ground.

We had arrived in the afternoon of October 2, the second day of the four-day "National Day" holiday which commemorates the founding of the Peoples' Republic of China (or the Communist government) on October 1, 1949. We could not get hold of our contact for housing so we decided to find a hotel for at least one night. The first hotel I called that was listed in our guidebook was no longer available to foreigners I was told by a Chinese woman in perfect English. The receptionist I called at the second hotel I inquired at told me the rate was more than twice as much as the one listed in our guidebook (the edition of our guidebook was just one year old). We hired a taxi to take us to the hotel, but the driver didn't really know where the street we were looking for was located. I thought that I had communicated with him fairly well with my rudimentary Mandarin language skills, but our map did not show us how to get to the street where the hotel was, and he couldn't find the street on his map. He would say, "Chang Yang Fangdian?" and I would say "dui" (correct). Five minutes later he was lost. We hired taxis two other times and they took circuitous routes that may have saved on time but also increased the fair significantly.

It cost us about $12 to get from the airport to our Shanghai hotel and it probably would have only cost us $8 to get to the hotel if our driver took us directly to the hotel. In the end, we were just glad to get there. Our hotel was apparently the only place for foreigners to stay within a few miles because I saw more foreigners there than anywhere else except the airport. The hotel has floor attendants immediately as you get out of the elevator to the floor where you are staying. Our floor attendant had a blue uniform like the rest of the hotel staff and I couldn't exactly figure out her duties except that she kept tabs on the guests and was there to help out with such room comforts as providing a new roll of toilet paper.

Shanghai will always be known to me as the place where things stop working. Aside from my laptop computer whose problems may have resulted from trying to load a pirated CD ROM in Hong Kong, everything else seemed to have broken down. The light in our bathroom stopped working as did the light above one of the beds. Karen turned off the light I was using to read with because it was above where she was trying to sleep. After she learned that the light closest to me, at the adjoining bed was not working. She tried to turn the light above her head on. It didn't work nor did anything else on the radio-like console built into our night table that operated various lights and a television. The day before I had plugged my American surge protector into the wall before plugging a current converter in and with a loud "pop" the surge protector was rendered useless. Perhaps my subconscious was trying to make me fit in.

After our fairly comfortable but slow train ride Y100 (for the both of us) from Shanghai to Nanjing we looked for a phone to call for a hotel room vacancy. I used one of the public telephone stands like we had seen in Shanghai. After I dialed the first two numbers I heard some tone repeated so I told the attendant what was happening by telling her the two numbers and then making the noise my self. She told me to dial "66" first and I did so but the number was either busy or didn't work. I never found out if the number worked because she took the phone from me and asked where I was calling. I told her the name in Chinese and she said something that intimated that the hotel didn't exist. She motioned for me to enter a building next to the phone stand and go up the stairs where I met three uniformed women. First I asked them if they had any vacancies and then I told them the names of the hotels I was looking for. They told me "bu renshi" (they had never heard of the places) and tried to help me but I couldn't understand what they were saying. I went back downstairs, but in order to get back to the phone I had to either rudely ignore the woman who had attempted to help me or try to explain "tamen [they] bu renshi." Rather than giving up, she continued to try and convey something to me until Karen and I finally realized that she knew of a hotel that we could go to for Y180 a night within five minutes walking distance of our location. Karen suggested that we should continue to call the hotels listed in our guidebook because the guidebooks were generally reliable when it came to a decent place to stay the night and they listed a couple of places in the center of town rather than some distance out of the center where we had been instructed to see how we could refuse the woman's help after she had tried so hard seemingly with nothing to gain.

After walking past four dead rats and twice as many more scurrying around on the side of the sidewalk and around some bushes that lined it, we reached the hotel. As we were walking into the hotel lobby, which made the hotel look more expensive than we were willing to pay, I saw a young American backpacker and asked him if he was looking for a place to spend the night too. He acknowledged that he was and we attempted to communicate with the front desk together. We eventually learned that the rooms on the upper floors of the hotel were less expensive than the ones on the lower floors and the backpacker, Marcel, speculated that it was probably because they didn't have an elevator. Marcel looked at their price sheet and discovered that triple rooms were less expensive than doubles in the upper rooms so we asked to see a triple. An attendant took us to a triple room (three beds) and it looked very nice so I said that Karen and I would take it.

After we paid for a few nights in advance, we were given a receipt instead of a key. We went back to the room that I was shown earlier, but I noticed the number didn't match the number on my ticket. After finding an attendant, we learned that our room was on the sixth floor, and yes there were no elevators. The number of the room we saw initially was in the 3100 range and the number listed on our receipt was 2605 broken down first by what building, "3" or "2", and then by floor "1" or "6" in our case. After we got to our room we realized that we had been shown a model room because the carpet on the floor of our room was filthy, the toilet seat was worn so bad in places that the wood, or particle board, underneath the finish was showing, and brown water came out of the sink when you turned it on. It was after Marcel saw our room which was across the hall from his that he mentioned that I might pay for a room one-night at a time in the future to which Karen reminded me that she had repeatedly told me the same thing before. Later we learned that the hotel was right next to train tracks and when trains went by rooms on the higher floors shook! Let this be a lesson to all assertive men.