[March, 1995] "Yoboseyo, welcome to Hanguk, the Hermit Kingdom." Koreans don't speak much English in Seoul, but it's even more difficult to find someone outside of the capital who speaks does. In Gyongju (Kyongju) and Andong, Koreans were quick to laugh at our difficulty in communicating a concept or a need because we couldn't speak Korean. Anywhere we were in Korea, a Korean person doing business with us that got frustrated with our inability to understand them would start talking to themselves, and sometimes us, for as long as several minutes.

Our first stop was a small city southeast of Seoul named Gyongju. Gyongju was the capital of the Shilla period (57 B.C.- 935 A.D.) in Korea and numerous historical sites, mostly burial mound sites and relics are found there. A story has evolved around the making of one of the relics, the largest preserved bronze bell known as Sacred Bell of Songdok the Great which dates from 771. This bell, also known as the Emille Bell, was the final of several attempts at constructing a bell with the perfect sound. To attain this perfection, it was deemed necessary that a young girl be thrown into the molten bronze which formed the bell. "Emille" (mother) is thought to be the lingering tone made when the bell is struck, a spell of sorts that remind us of the sound of the poor girl crying for her mother as she was thrown into the molten metal.

Two especially important religious sights in Gyongju are the Sokkuram Grotto and Pulguksa (Temple). Sokkuram Grotto is regarded as one of the finest examples of Buddhist art in Korea and dates from 751. The Grotto though itself not too spectacular when compared to the wats of Thailand, is reached by a serene mountain path-that is if the hordes of visitors to this important site are absent. In the center of the Grotto, a large statue of a seated Buddha is sheltered by a wall of glass and a sign that asks visitors not to take photographs (I captured the scene on video instead). The Grotto was part of an experience in Korea, as well as Japan and later China, that led me to believe that Buddhism is not practiced with the same comfort and tolerance as it is in Thailand. Nor does it have the same proportion of serious adherents or is it interwoven in the fabric of society to the same degree as in Thailand.

Two especially important religious sights in Gyongju are the Sokkuram Grotto and Pulguksa (Temple). Sokkuram Grotto is regarded as one of the finest examples of Buddhist art in Korea and dates from 751. The Grotto though itself not too spectacular when compared to the wats of Thailand, is reached by a serene mountain path-that is if the hordes of visitors to this important site are absent. In the center of the Grotto, a large statue of a seated Buddha is sheltered by a wall of glass and a sign that asks visitors not to take photographs (I captured the scene on video instead). The Grotto was part of an experience in Korea, as well as Japan and later China, that led me to believe that Buddhism is not practiced with the same comfort and tolerance as it is in Thailand. Nor does it have the same proportion of serious adherents or is it interwoven in the fabric of society to the same degree as in Thailand.

The original Pulguska was built from 751 to 774 and burned by Japanese invaders under Hideyoshi Toyotomi in 1593. Some of the buildings were rebuilt, but most of the reconstruction which does not come close to representing the original 80 buildings were rebuilt between 1969 and 1973. Here we saw Korean tourists many of whom were worshipping in the main temple, older women and men dressed in Hanbok (traditional dress), and several Buddhist nuns dressed in gray robes with shaved heads.

hanbok dress

hanbok dress

We were surprised when walking through the streets of Gyongju with the weather dipping below 40( at times, at the sight of young women and girls dressed in mini-skirts, sometimes accompanied by short fur jackets. This was in contrast to the relative conservatism we experienced in Thailand and certainly in the Philippines. There were magazines in stores and at booths that featured scantily clothed women on the covers, but like the Philippines, there were no real pornographic magazines to be found.

It was largely because of my disappointment in Gyongju, the area I would dub the "Land of Historic Mounds", that I searched for another place outside of Seoul that might reveal something about Korea's history and culture. Searching through our guidebook, I found Hahoe. Hahoe was supposed to be a small town near Andong, somewhere between Gyongju and Seoul, where the community lived and looked much as it did in the last dynasty of Korea, Choson, which lasted from 1392 until it came to an end in 1910 at the official beginning of Japanese colonial rule).

Language proved a difficult barrier in our attempt to get to Andong, but it became an insurmountable barrier in getting from Andong to nearby Hahoe. I found a Korean man who knew enough English to tell me where I could get tickets for Andong, and at the bus station I was able to use my limited Korean language skills(!) "Kyongju, Andong" to get us tickets, but then we got on the wrong bus. Our penalty for listening to a conductor who told us to get on the wrong bus, though it was going to Andong, was a 35% increase in our original fare; a long talk (well sort of) with a friendly bus driver who knew just a few words more of English than we knew of Korean though that didn't stop him; and a significantly longer journey than the route we had bought tickets for.

When we finally arrived in Andong, I thought I would do my wife a favor by looking for a hotel by myself while she waited near the bus station with our luggage. It's amazing how difficult such a task can be when you can't read "hotel" in Korean. Finally a voice from behind me said, "you look lost." My embarrassment was overcome by the joy of having seemed to feel comfortable with the surroundings offer help. It turned out that the voice belonged to a young man from San Diego who had been living in Andong for about nine months and was only too glad to help me since I was the only Westerner he had seen in months other than his roommate [he was teaching English: though the linked letter was not authored by him]. He gave me my first real lesson about Korea: that yogwan (a traditional Korean inn) can be distinguished by a symbol at the top of one's sign which looks like a "c" turned on its side with three swiggly lines rising up from it much like an abstracted picture of a bowl with steam rising out of if. Finally, I could read some Korean! Eventually his helped led us to a yogwan that turned out to be less expensive and nicer than the hotel we had stayed at in Gyongju.

Before we left Gyongju, we had a couple of traditional Korean meals. Each time, unfortunately, we didn't know how to order so we ordered two meals, each of which could have fed two to four people. When the waitress brought us the meal during our second experience, she showed us how to properly eat a Korean meal. We were each given several bowls of cold food and a small stove on which meat was cooked and kept warm. We were suppose to take one of several pieces of rectangular lettuce leaves and deftly place the contents of the several bowls together with the meat on top of it then fold the lettuce "sandwich" using chopsticks. It appeared to be an easy task when she demonstrated it for us, but when our chance came to repeat the lesson we learned failed miserably. I was forced to use my hand much of the time which made me feel like a kid. I could only wonder what the Koreans who could see me thought realizing that it was considered rude to eat as I did. Luckily, when we sat down for a late lunch in an upstairs restaurant in Andong, there was a sliding partition in between us and a small group in the next room though there were several tables in our area. I think I enjoyed this meal more than any other in Korea because I could enjoy Korean cuisine with the dexterity of a child, but the stomach of an adult and nobody could see me. Karen preferred a spicy noodle soup that she first tasted in Gyongju.

|

We saw more short-skirted women in nearly freezing weather in Andong, the best dressed bankers I've ever seen, and women with coats that made them look like hunched-backs. The men at a large bank we went into to exchange money were generally dressed nicer than the conservatively dressed American businessmen we were used to seeing in San Francisco, but all the women at this same bank were wearing identical, boring uniforms (I also observed the amazing ability Koreans have of counting wads of cash with great speed). I saw several women walking down the street with a hump on their back. After hearing a baby crying as one of these women walked past me, I realized that they were carrying babies on their backs with the heads completely concealed by their winter jackets.

We saw more short-skirted women in nearly freezing weather in Andong, the best dressed bankers I've ever seen, and women with coats that made them look like hunched-backs. The men at a large bank we went into to exchange money were generally dressed nicer than the conservatively dressed American businessmen we were used to seeing in San Francisco, but all the women at this same bank were wearing identical, boring uniforms (I also observed the amazing ability Koreans have of counting wads of cash with great speed). I saw several women walking down the street with a hump on their back. After hearing a baby crying as one of these women walked past me, I realized that they were carrying babies on their backs with the heads completely concealed by their winter jackets.

|

Having paid a heavy price for our education, we realized upon arriving in Seoul that we should hire a taxi to take us to the center of town and help us locate a yogwan. We faired better with our taxi driver's help, but not much so. When I tried to explain to him what we wanted and that we didn't have reservations at any place he looked perplexed. He explained to me in broken English that there were numerous yogwans in the center of Seoul so I asked him to drop us off at any one of them. We reached the center of Seoul and it took a short while for him to find a yogwan. He then got out of the taxi and went inside the yogwan to help us out. He came back after a short while and said no rooms were available. Then he drove us around for a short while before taking us back to that same spot where the yogwan was. Realizing that our fare was continuing to escalate, I asked him to drop us off. He did so, but with a reluctant look on his face. He was clearly upset at having failed us.

Several times we noticed that Koreans have a unique sense of responsibility that we haven't experienced elsewhere. On another occasion, a man tried to help us at a subway station ticket machine and lost some money that I gave him to the machine in the process. He then paid for our ticket with his own money and walked away without accepting my money for the ticket. These two experiences and the bus experience (from Gyongju to Andong, see above)-where the driver knew exactly what had happened and knew the conductor had caused the mix up in the first place, but thought it natural for us to pay since we had taken the wrong bus-characterized something unique and consistent in Korean society.

It took me some time to find a yogwan while again Karen waited near our bags, but this time I knew what sign to look for. Before we found a room, I must have entered about five yogwans though it was the end of February (hardly the tourist season) where there was apparently no room available and I began to recall the difficulty black Americans were known to have under similar circumstances in their own country a couple of decades earlier. Yogwans are smaller than Western style hotel rooms, but we both liked them much more especially since the weather was cold and the floor were heated with ondol (a traditional heating system of flues which ran under the floors ).

MAN FACES ARREST FOR STEALING WOMEN'S UNDERWEAR

article from the Korean Herald News

An arrest warrant was sought Friday for Kang Ho-chul, 36, who allegedly stole over 500 pieces of women's underwear, by the Seoul Noryanggin Police. Kang will be charged with violation of the Law on Added Punishment of Specific Crimes.

According to the police, Kang secretly entered the lodging room of a Lee 22, in Taechi-dong, Southern Seoul, on Feb. 13 [1995] at about 6:20 p.m., and stole some 20 articles of undergarment. The total number of underwear he stole from similar lodging rooms of unmarried women in the Kangnam area since Jan. 1992 is said to be over 500.

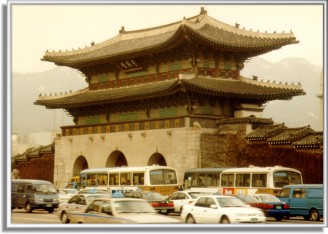

Kwanghwamum

Kwanghwamum

The Western term "Korea" was derived from one of the Korean political periods known as Koryo which lasted from the tenth century to the fourteenth century when it was replaced by the Choson Dynasty. It was during the Choson Dynasty that Seoul became the capitol of Korea and many of the important palaces of that period as well as two of the old city gates remain. The center of Seoul is marked by Namdaemun (South Gate) in the southern corner and Tongdaemun (East Gate) in the eastern corner (the fortified wall of Seoul originally had four main gates, one at each compass point). These gates were traditionally the locations of marketplaces which flourish even today. Some of the palaces that are located in the center of Seoul are Toksugung, Ch'angdokkung, Ch'anggyonggung, and Kyongbokkung. The furnishings from these palaces have been placed in museums and they exist as empty shells that nevertheless are historical architectural monuments to Korean culture under the Choson Dynasty. These palaces are also the favored locations of wedding couples for their wedding photos.