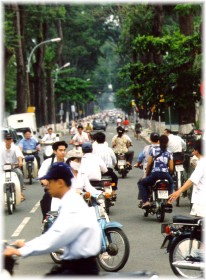

[June, 1999]. The streets of Vietnam's two most important cities: Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon or Sai Gon) and Hanoi (Ha Noi) are more active than any I have ever seen in my life. There appears to be an unspoken belief that if traffic is delayed too long, life will cease. It's something like the goat, killed ceremonially, who has his jugular slit and is then left to run out the few remaining moments of his life. The traffic moves constantly like a stream of ants. Stoplights are only obeyed if absolutely necessary. Traffic police in Ho Chi Minh City, dressed in a sort of peach colored uniform to distinguish them from the dark green uniforms of the public security force and plainclothes police, do exist but their need seems to be in doubt. As soon as the cross traffic dwindles the push forward begins, motorbikes are still jockeying for position when the traffic begins to surge forward again. For the moment, the need for constant movement outweighs the need for collecting traffic fines for the state coffers.

[TRAFFIC IN HO CHI MINH CITY]

is visibly more affluent than Hanoi, there are more cars and trucks and the stores are more upscale, but life on the streets of both cities is frenetic. Driving in Vietnam can be nerve racking for the uninitiated driver whether you are a driver or simply a passenger. Vietnamese honk their horns long and hard to warn pedestrians, bicycle riders, motorbike riders, and cars that they are passing. Since the rules of the road are so liberal and the range of speeds so wide, this sort of honking is incessant. On the other hand, road rage as seen on the roads of America seems a rarity. We saw almost no accidents though a friend saw five during the same time. Ironically, within minutes of finishing writing this we came across a short traffic jam where a uniformed policeman was moving a motorbike off the road following some accident.

is visibly more affluent than Hanoi, there are more cars and trucks and the stores are more upscale, but life on the streets of both cities is frenetic. Driving in Vietnam can be nerve racking for the uninitiated driver whether you are a driver or simply a passenger. Vietnamese honk their horns long and hard to warn pedestrians, bicycle riders, motorbike riders, and cars that they are passing. Since the rules of the road are so liberal and the range of speeds so wide, this sort of honking is incessant. On the other hand, road rage as seen on the roads of America seems a rarity. We saw almost no accidents though a friend saw five during the same time. Ironically, within minutes of finishing writing this we came across a short traffic jam where a uniformed policeman was moving a motorbike off the road following some accident.

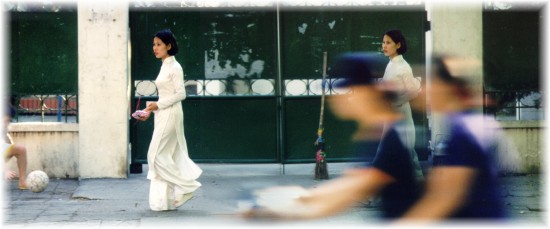

[OFFICE WORKERS ON THEIR WAY TO WORK, HO CHI MINH CITY]

, pronounced "ou yai", are popular in the South, but not so much in the North. It is one of

those fashions that seem to only have a last leg on life due to the global popularity of western

dress. It seems designed specifically for the younger, Vietnamese female form which is often

beautifully lean but well proportioned without a hint of emaciation as is so perversely admired

in western high fashion circles. Made of silk or a less expensive synthetic material, the áo dài

is tightly fitted on the upper body, with long sleeves and the bodice drapes down in the front

and back nearly to the ankles. The sides are slit up to a few inches above the hips and the

sheer material often reveals panties from where this opening slit occurs though this display is

only vulgar in the vulgar, uninitiated male mind. The material that drapes down in front and

back of the loosely fitted pants creates animation in the fashion with varying forms of movement

that is ingenious. Often an embossed, colored top is matched with an embossed white bottom,

though we learned that a matching colored top and bottom is the current fashion trend.

Apparently resurrected from an untimely death at the more zealous tenets of communism, today

the áo dài has a role in Southern Vietnamese women's fashion something akin to the world role

of the western business suit for men. I asked one woman if she thought Vietnamese women like to

wear the áo dài and she told me she thought most Vietnamese like the uniquely Vietnamese fashion.

, pronounced "ou yai", are popular in the South, but not so much in the North. It is one of

those fashions that seem to only have a last leg on life due to the global popularity of western

dress. It seems designed specifically for the younger, Vietnamese female form which is often

beautifully lean but well proportioned without a hint of emaciation as is so perversely admired

in western high fashion circles. Made of silk or a less expensive synthetic material, the áo dài

is tightly fitted on the upper body, with long sleeves and the bodice drapes down in the front

and back nearly to the ankles. The sides are slit up to a few inches above the hips and the

sheer material often reveals panties from where this opening slit occurs though this display is

only vulgar in the vulgar, uninitiated male mind. The material that drapes down in front and

back of the loosely fitted pants creates animation in the fashion with varying forms of movement

that is ingenious. Often an embossed, colored top is matched with an embossed white bottom,

though we learned that a matching colored top and bottom is the current fashion trend.

Apparently resurrected from an untimely death at the more zealous tenets of communism, today

the áo dài has a role in Southern Vietnamese women's fashion something akin to the world role

of the western business suit for men. I asked one woman if she thought Vietnamese women like to

wear the áo dài and she told me she thought most Vietnamese like the uniquely Vietnamese fashion.

[WOMAN WEARING AN ÁO DÀI IN HANOI]

Then there are some other uniquely noticeable Vietnamese fashions of lower culture. Long-legged, short sleeved pajamas and more rarely, lingerie is worn publicly by women in the North and South, though more so by women in the North and usually only near the house or home business. The informality of this attire cannot be overstated. Occasionally, to my undersexed delight, I would see a woman wearing such "evening" wear without a bra on. Both farmer- fisher-women and city women wear handkerchiefs or some similar cloth over their faces if working around traffic or commuting. Farmer women often wear scarves tightly around their heads underneath conical hats, which when worn with the scarves around their faces, leave only a slit visible for their eyes. Surprisingly, these heavily covered women would refuse to be photographed as much as anyone. Women on motorbikes also wear long gloves that extend up past their elbows. We were told this was to help women keep their skin fair, but it seem also to be an effort to help fight against the dust and pollution of the roads in Ho Chi Minh City. The rage of city women in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City are hats the designs of which seem to be left over from the departed French colonials of the 1950s. Men in both North and South Vietnam wear western attire. Green pith helmets worn by the Vietnamese army are very popular amongst the men in North. Also conspicuously a part of contemporary Vietnamese fashion are medicated squares of white tape on temples serves to provide relief against headaches.

In the East money is king. I was reminded of this our second night in Vietnam. Traveling light, more so with every trip, we only brought one luggage-type bag and a school backpack. So we only had the bare essentials. Our clothing consisted of lightweight t-shirts, and very casual pants. We brought along tennis shoes, but only for the plane ride. We wore simple rubber sandals every day. We went to a restaurant that our guidebook had recommended - though it did not mention that there should have been a dress code even if it wasn't enforced. When we got out of the taxi, I was already embarrassed. You could tell by the uniforms of the male employees that it was a fancy restaurant where people just didn't wear the sort of clothes we had on. I kept warning Karen as we entered, but she was dismissive, so I muttered something of my concern to one of the restaurant workers as Karen told me that we would be informed of any dress code so we shouldn't worry. Fortunately the crowd of mostly expatriate-business people grew after we had been dining at the restaurant for some time, so we were spared too much recriminations by the other, finely dressed customers. At the end of our meal, we were handed our exorbitant bill, by Vietnamese standards, of US$39.92.

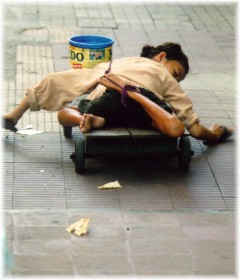

[CRIPPLED WOMAN BEGGING FOR MONEY, HO CHI MINH CITY]

In both Cambodia, where we made a brief visit, and Vietnam, young adults are seen throughout missing limbs. In Cambodia the signs and classes along village roads instructing the population about landmines left over by the Khmer Rouge make it clear where the limbs have gone to, but Vietnam's victims are not so easily explained. A man sells postcards and books on the streets of an upscale area of Ho Chi Minh City. He shows me a picture of a young woman and two children saying this is his family. In empathy, I ask him if he has a map. He maneuvers one out of the bag he has hanging from a strap around his neck. He drops it, but refuses to take it back when I say I don't want it for the exorbitant sum, losing site of my initial intent, charity. People say you learn more about yourself and about your own culture when visiting other countries. I often discount this idea, but maybe I shouldn't be so dismissive. A woman lying on her stomach pushes herself along on a flat cart with sandals on her hands. I only notice her after she grabs my pant leg and demands some money. Looking down, I see that her legs are twisted in unusual shapes, perhaps from polio or some similar disease. Another man missing one leg and sitting on the narrow stretch of sidewalk beckons me to give him money as we pass. I pray he will not grab my leg as we pass. Fortunately he does not. A few days later I see a man hop across the street onto the sidewalk and then lean against the wall of some building as if he is glad he can finally rest. He has only one leg and no arms.

[VIETNAMESE CURRENCY]

Vietnam is the first country I've been to where coins don't exist. Technically the coins do exist, but I only found them in sets attached to paperboard in a plastic wrapper for sale as a novelty item at the airport at a cost several fold their face value. During my visit, the dong was exchanged at a rate of about 13,900 for one dollar. This means that with just under $72.00 the exchange rate was about a million dong. Bills commonly circulate in denominations of 200, 500, 1000, 2000, 10,000, 20,000, and 50,000 dong or ranging in value of 1.4 cents to $3.60 and they all have bear the likeness of Uncle Ho (Ho Chi Minh). At the moment, the U.S. dollar also figures prominently in the Vietnamese economy. While exchanging travelers' checks at a bank, I read a notice advising customers that only a small amount of businesses are permitted to accept U.S. dollars as currency in their transactions. We found this notice to be a formality widely ignored. Where the price of goods is often left unmarked to permit negotiation, prices are often quoted in U.S. dollars and even where prices are marked in upscale tourist venues, the price would typically be in U.S. dollars. You could request to pay in dong, but it merely meant that the widely respected exchange rate of the day would be applied and you would use the local currency without favor or disfavor falling on either party.

I remember that before we left the U.S., I had read that what I believed to be an inordinate amount of the American workforce consists of sales people. When we arrived in Vietnam, I was even more surprised to see how many people were engaged in selling something, anything from stores or on the streets of Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. Maybe it's the youth of the population that makes it seem so dynamic. Vietnam's population is extremely young. In 1998, 49.6% of the population was under the age of 19 years of age. People work very hard in Vietnam to eke out a living selling anything. There were more than two dozen shops just selling shoes in one square block of Hanoi. So much of life in Vietnam happens outdoors: eating on foot-high plastic stoops of chairs; Hair cuts which come with nose-hair cuts and ear cleanings (the one in-door salon offered the male customers a clothed massage by two, uniformed women); fruit sales; sidewalk-seamstresses/tailors; Games of Chinese/Vietnamese chess or cards everywhere; wood stands from which raw slabs of meat for sale; lottery vendors; bicycle repair shops on corners; live fowl sold and slaughtered in markets that take over whole sections of streets; cyclo drivers paused beside the side of the road half on the sidewalk and half on the street; groups of motorbike owners looking to earn a small bit of money driving someone somewhere; money-changers who pull out wads of bills from their purse to advertise to a passing foreigner; lounge chairs set up on sidewalks that act as a poor person's front lawn; and in the North, men sit or squat smoking large, bamboo water pipes. These scenes can be found in much of East Asia, but in Vietnam it is more dynamic, more intense. Even front wall-less living rooms often open out into the streets in this hot and humid country where privacy seems only to be had at a premium expense.

[FLOWERS OF HANOI]

We asked our hotel clerk in Hanoi about all of the farmer women who show up in droves in the city every morning when everyone else is waking up. He said they take the bus or train and that they come from very far out in the province. He added that they sometimes sleep on the side of the road during their journey to the city. A couple of public security (police) drive through the streets of Hanoi's old quarter of dilapidated French architecture policing the economy. They ride on a discolored, light-blue motorcycle and half car slightly reminding me of old World War II movies where the Nazis would ride in such vehicles. A couple of ladies see the police ride by, quickly take their small plastic chairs and throw chairs on the other side of some bushes just behind them, out of view. They begin to lift their display boards full of cigarettes to hide them as well before they realize the police did not see them through the traffic. I smile knowingly at one of the women and she smiles back now that the fear has subsided. We see farmer women every morning with bunches of bananas, sitting on the closed storefront across the street from our hotel. We are told that they are permitted to sit until 7:00 a.m., but then have to keep moving, selling their produce on their feet or else they will get in trouble with the public security.

I asked a woman at a clothing shop in Ho Chi Minh City about the children selling stamps, books, and postcards who proliferate around areas where foreign tourists can be found. She told me they attend school in the nighttime so they can sell things during the day. She also suggested that their parents made them sell things during the day because the parents were lazy.