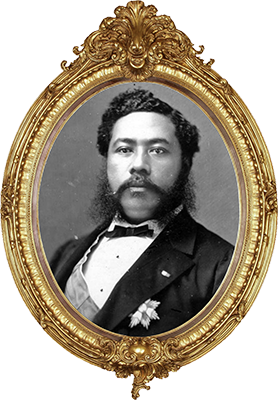

King Kalakaua |

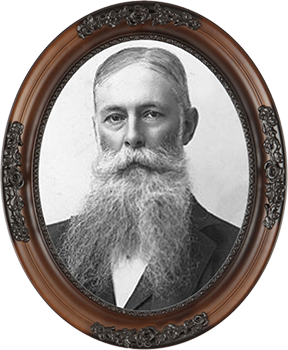

Queen Lili'uokalani |

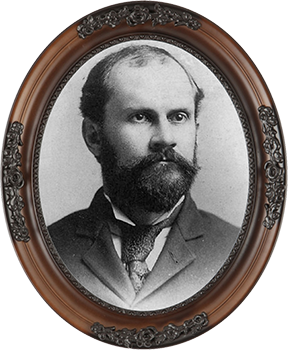

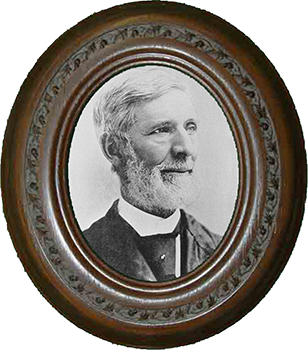

Sanford Dole |

Lorrin Thurston |

For many years our sovereigns had welcomed the advice of, and given full representations in their government and councils to, American residents who had cast in their lot with our people, and established industries on the Islands. As they became wealthy, and acquired titles to lands through the simplicity of our people and their ignorance of values and of the new land laws, their greed and their love of power proportionately increased; and schemes for aggrandizing themselves still further, or for avoiding the obligations which they had incurred to us, began to occupy their minds. So the mercantile element, as embodied in the Chamber of Commerce, the sugar planters, and the proprietors of the 'missionary' stores, formed a distinct political party, called the 'downtown' party, whose purpose was to minimize or entirely subvert other interests, and especially the prerogatives of the crown…they would be bound by no obligations, by honor, or by oath of allegiance, should an opportunity arise for seizing our country, and bringing it under the authority of the United States.

[Deposed Queen, Lili'uokalani]

[Deposed Queen, Lili'uokalani]

Unquestionably the constitution was not in accordance with law; neither was the Declaration of Independence from Great Britain. Both were revolutionary documents, which had to be forcibly effected and forcibly maintained.

[Lorrin A. Thurston referring to the Bayonet Constitution he helped to impose on King Kalakaua]

[Lorrin A. Thurston referring to the Bayonet Constitution he helped to impose on King Kalakaua]

After Judd was eventually purged in 1855 for his rabid efforts to get the United States to annex the Kingdom, the missionary group, consisting of ABCFM missionaries, laypersons, their offspring and allies connected primarily through the Punahou School, was increasingly challenged by Native Hawaiians and other haoles with competing interests. Two of Judd's protégés, whose tenure in government outlived his, were William Little Lee and Charles Reed Bishop, distant relatives and friends from New York who came to Hawai'i via Oregon together. Lee, a graduate of Harvard Law School, offered the legal skills Judd needed so was appointed judge of O'ahu and enlisted to help draft the architecture for the Kingdom's judicial system. He also served on King Kamehameha IV's Privy Council. Ironically, Lee was one of those who helped push Judd from power, according to Dougherty.

Bishop lacked the fortuitous training that Lee possessed but he, who along with Lee played "bat and ball" at Punahou on Saturdays with the enthusiastic youngsters at the school, made the most of his connections (Bishop later served as trustee of Punahou from 1867-1891). The same year he arrived in Honolulu, 24-year old Bishop met his future wife, Bernice Pauahi Paki, at a party thrown by Amos Starr Cooke, when she was 15-years old. Cooke and his wife, Juliette, were secular employees of the ABCFM and ran the Chiefs' Children's School (later called the Royal School) where converted children of the ali'i and every Hawaiian monarch after Kamehameha III received their education isolated from other Native Hawaiians. Selectively pious, the Cookes helped cultivate Bishop's three-year courtship of Bernice against her parents' wishes that she marry an ali'i. Bernice was the Great Granddaughter of Kamehameha I and his last surviving heir after Kamehameha V died in 1872 gaining rights to the royal lands still reserved for the monarch since the Mahele, some 11% of all land in Hawai'i. In 1858, Bishop established the first bank in the Kingdom, Aldrich & Bishop (later Bishop & Co.), and held a monopoly for more than two dozen years (his bank served as the origins for the First Hawaiian Bank (1960) which is still Hawai'i's largest bank).note

John Owen Dominis was another haole who married Hawaiian royalty. The son of a sea captain, Dominis married the last monarch of Hawai'i, Queen Lili'uokalani. As a boy, he and other boys who attended a schoolhouse next to the Cookes' residence would climb a fence separating the two schools to spy on the royal children, including Lili'uokalani. Later, when they were both adults, they met while Dominis was on the staff of Kamehameha V and fell in love. They had no children though Lili'uokalani adopted her husband's bastard child after Dominis and the mother, her servant Mary Pudry Lamiki 'Aimoku, died.

Hawai'i's economy has never been diverse, and, as we saw from the fortunes of Lee and Bishop, the skills of the enterprising civilization that Bingham, Richards and Judd had foisted on the Native Hawaiians took time to develop. Sandalwood ('iliahi), which grows wild on the island was highly valued in China, dominated the Islands' foreign trade from roughly 1810 until it was exhausted by over exploitation around 1830. Hawai'i had become an important wintering port for vessels trading with China soon after the Islands were discovered, but whaling in the Pacific Ocean exploded in the first half of the nineteenth century with the discovery of hunting grounds in the Sea of Japan, South Pacific and the Arctic. Whale oil was used for heating, lamps and in industrial machinery. The two important ports of Honolulu (O'ahu) and Lahaina (Maui) owe their early growth to the whaling industry. Like sandalwood before it, whaling declined though this time due to the discovery of oil fields on the mainland beginning in 1859.

Sugarcane (ko) was different. It grew easily in Hawai'i, only took two years to grow to harvest, and was sustainable. Haoles with capital only needed land, a market, and a labor force. Judd had solved the first problem years earlier. The Civil War destroyed sugar production in the American South but Hawaiian growers still had to overcome a tariff on exports to the US. Warfare to unify the islands and diseases introduced by the haoles such as measles, whooping cough, dysentery and influenza, and to a lesser degree, emigration, were responsible for the precipitous decline of Native Hawaiians from an estimated 400,000 at the time of Cook's discovery to 40,622 "Natives and Half-Castes" in 1890, or a reduction to one-tenth of its pre-European contact size.

The first efforts at stabilizing the labor supply needed for sugar plantations targeted Chinese labor. The influx of laborers was so great that by the 1880s the Islands' taro growers began to switch to growing rice to feed them. In 1878, Portuguese started emigrating to the Kingdom to work on the plantations. They were treated differently from the Chinese, who were often whipped, and other Asian groups that followed because they were European. The Portuguese were encouraged to immigrate as families, were given an acre of land, a house and improved working conditions, in particular, they were often chosen as overseers (luna) of other plantation workers. Because the Portuguese were needed, their Catholicism was tolerated and strengthened the community that the Protestant missionaries had earlier suppressed. They also introduced foods such malasadas, pao doce and Portuguese sausage to Hawaiian cuisine. The 'ukulele was adapted from the Portuguese barguinha and cavaquinho. The greatest change in the makeup of the Island population during this period, though, was encouraged by the US Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 which precipitated the influx of Japanese labor. The

1890 Census provides us with this breakdown of sugar plantation workers:

| Japanese | 8,024 | 43.7% |

| Chinese | 4,517 | 24.6% |

| Portuguese | 3,017 | 16.4% |

| Native Hawaiians | 1,873 | 10.2% |

| South Sea Islanders | 433 | 2.4% |

| Americans | 101 | 2.7% |

| British | 80 | |

| Other nationalities | 314 | |

| Total | 18,359 | 100% |

The obstacle of US tariffs, held more direct implications for the Kingdom's politics. After the last of Kamehameha's direct descendants, Lot Kapuaiwa (Kamehameha V) died in 1872, successive Hawaiian monarchs were elected. Ali'i David Kalakaua was the second king to be elected after contesting the election against Queen Emma (granddaughter of John Young and wife of King Kamehameha IV). Sugar interests backed Kalakaua because he secretly agreed to cede Pearl Harbor to the US in exchange for a free-trade agreement. The resulting Reciprocity Treaty was concluded in 1875 and went into effect near the end of the following year, but did not include a Pearl Harbor provision as initially conceived.

Instead, the US was granted the "exclusive privilege of entering Pearl Harbor and establishing there a coaling and repair station" for its navy when the treaty was renewed in1887. The effect of the treaty was immediate and substantial, exports of raw Hawaiian sugar increased from 13,000 tons in 1876 to 229,000 tons in 1898.

Sugar brought Clause Spreckels to the Kingdom. A technology entrepreneur and sugar baron whose capital far outsized that of any of the haoles' on the Islands, he was an outsider who was both a monarchist and rich, so his independence was anathema to annexationists. After having originally immigrated to the US from Germany, Spreckels arrived in Honolulu in 1876, a month before sugar was allowed into the US duty free. He already owned the California Sugar Refinery and aimed to use his fortune to leverage himself into the Hawaiian sugar plantation business. Spreckels made a loan of $34,000 to Prime Minister Walter Murray Gibson with the latter's property holdings on Lana'i serving as collateral. He also loaned Kalakaua $40,000 secured by royal lands. Spreckels purchased 24,000 acres of royal lands on Maui and loaned the ali'i Ruth Ke'eklikolani $60,000 as part of the package. By 1886, he held $700,000 of the Kingdom's debt and commensurate political influence as a top adviser to Kalakaua and Gibson to go with it.

Prime Minister Gibson was an adventurer who, before coming to Hawai'i, had served a year imprisonment in the Dutch East Indies for inciting a Sumatran raja against Dutch colonial rule there. He arrived in the Kingdom as an envoy of the Mormon Church with the mission of revitalizing the church on the island of Lana'i. In the process he used church funds to purchase lands in his own name. After Mormon officials learned that he had defrauded the church he was excommunicated, but he retained title to the lands.

Gibson learned to speak fluent Hawaiian and moved to Honolulu where he began publishing a small Hawaiian-language paper, Ka Elele Poakolu, and purchased the Pacific Commercial Advertiser in 1880. He was so effective in utilizing these newspapers for his populist propaganda that he was one of only three haoles elected to the Legislature in 1882--27 missionary-sugar industry candidates were defeated. The missionary-sugar industry tried to win Gibson over with political inducements but he resisted. As chairman of the Finance Committee, Gibson delivered a report to the Legislature condemning the Finance Minister for loaning $250,000 in public funds to Bishop & Co.--at the time, Bishop was a member of the House of Nobles and on the Privy Council. Gibson also denounced "cabinet ministers and their political cronies among Missionary Families and other long-established haole groups" involved in conflicts of interests with the business concerns.

With Gibson and Spreckels at his side, Kalakaua was further emboldened to chisel away at the legacy of political power Judd had created for the missionary group. During his tenure, Kalakaua appointed 11 Native Hawaiians while the three previous kings had appointed only two. The missionary group's opposition to the King and top supporters, Prime Minister Gibson and advisor Spreckels, came up short in the election of 1886. Only 10 of their candidates won, and four of these were Native Hawaiians. The government's party won 18 seats. Kalakaua rewarded Gibson by naming him both Premier and Foreign Minister.

The missionary group had already been holding strategy meetings before the election, but afterwards they gained more urgency and their discussions a greater need for secrecy as they began to consider extralegal tactics in earnest. It is difficult to clearly identify the core members of the missionary group because their meetings were secretive, those actively involved outside of a handful of individuals changed over the eight years of their most active period from 1885-1893, and it was incumbent upon the group to exaggerate their numbers to foster a belief in the legitimacy of their efforts. Even within the missionary group, unanimity of thought did not always prevail. Some individuals might have been against annexation, others were angry over corruption in the government and wanted changed but differed over how to effectuate it and how far it should go.

The missionary group’s leaders were Sanford Dole and Lorrin Thurston, both children of missionaries and Punahou alums, and included William Wisner Hall, William Owen Smith, William Ansel Kinney, Charles Reed Bishop, Samuel Mills Damon, William Richards Castle, William De Witt Alexander, Joseph Ballard Atherton, Edward Griffin Hitchock, James A. King, Samuel Gardner Wilder, Peter Cushman Jones, Paul Isenberg and William Harrison Rice. Sanford Dole was the son of Daniel Dole, who served as Punahou's first teacher and principal from 1841-1854. The younger Dole was first elected to the Legislature in 1884 and reelected in 1886. Lorrin Thurston was the grandson of Asa Thurston, an ABCFM missionary who arrived in the Kingdom on the Thaddeus with Hiram Bingham. Lorrin Thurston spoke Hawaiian, had been an overseer on a sugar plantation in Maui before attending Columbia Law School and began practicing law upon returning to Hawai'i. He was elected to the Legislature for the first time in 1886. William Owen Smith was a son of ABCFM missionaries, and both he and William Ansel Kinney were Punahou alums and Thurston's law partners. William Wisner Hall was also a son of an ABCFM missionary and Punahou alum.

Samuel Mills Damon's maternal grandfather helped to found the ABCFM and his father was a missionary as well. Samuel was Charles Reed Bishop's partner in Bishop & Co. Damon's brother-in-law, Henry Perrine Baldwin, co-founded the Big Five firm, Alexander and Baldwin, with Samuel Alexander. Baldwin and Alexander where both the sons of ABCFM missionaries and Punahou alums. Their business centered on sugarcane

production. Samuel married Martha Cooke, daughter of Amos Cooke, and Henry married

Samuel's sister, Emily. Samuel's brother, William De Witt married Henry's sister, Abigail Baldwin. Another of Samuel's brothers, Charles, married Helen Thurston, the sister of Lorrin Thurston, and granddaughter of Asa Thurston. All had attended Punahou.

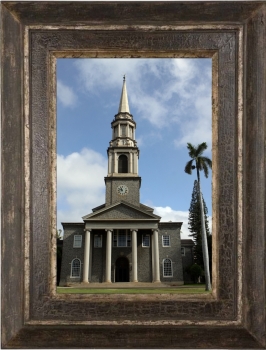

|

Central Union Church at Punahou and Beretania Sts. (three blocks west of Punahou School). Though built in the 1924, the congregation dates from Seamen's Bethel, founded in 1833--later renamed the Bethel Union Church, which merged with another branch of the same church in 1887. Congregants included Charles Reed and Bernice Bishop. |

James A. King had been in charge of Samuel Gardner Wilder's shipping operations for years. Wilder was married to Mary Kina'u Judd (G.P. Judd's daughter). Wilder's younger sister, Harriet, married Joseph P. Cooke, Amos Starr Cooke's son.

Peter Cushman Jones was a trustee of Punahou and a partner and president of yet another Big Five firm, C. Brewer & Co. His partner was Henry A.P. Carter, a Punahou trustee, who had married to Judd's daughter, Sybil Augusta Judd. As Hawai'i's minister to the United States, Carter had negotiated the Reciprocity Treaty in 1875 and its extension in 1887. Charles Reed Bishop was an investor in C. Brewer & Co. Paul Isenberg was a German immigrant who ran the Big Five firm, Hackfeld & Co (later known as Amfac, or American Factories). Isenberg was married to Hannah Maria Rice a Punahou alum. Her father, William Harrison Rice, was an ABCFM missionary and teacher, and business manager at Punahou.

Already in 1884, Sanford Dole and William Owen Smith had purchased the editorial rights of the Daily Bulletin from its owner, Walter Hill, so Lorrin Thurston could serve as the missionary group's public mouthpiece. Here Thurston echoes nostalgically the Judd era arguing: "It is a misfortune to this Kingdom that its constitution does not provide for utilizing the opinions of its foreign population [i.e., Americans, Germans and British citizens] so that the progressive ideas of the older culture maybe incorporated with the 'united wisdom' of the national representatives in the administration of the affairs of state."

Gibson's Pacific Commercial Advertiser responded: "The truth is, however, the Opposition objects to the Constitution because it grants the majority of the people the right to control the Government through the Legislature and guarantees the independence of the Crown."

In his memoirs, which Thurston urged him to write to capture revolutionary events through the revolutionary's eyes, Dole's story is self-righteous and cleansed of any self-incrimination. When one looks at Dole's arguments for what spawned action and the changes imposed by the missionary group's coups, however, it is clear that the motivation was nothing more than the racism of their progenitors, ABCFM missionaries Bingham, Richards and Judd, nurtured in their childhood, and indignation over challenges to what this tightly-knit group of haoles grew to believe was their birthright.

Dole claims that the precipitating factors for a coup the missionary group engineered against Kalakaua in 1887 were:

- A bill to license an individual to sell opium [only to Chinese residents or others for medical purposes with a prescription] duly passed by the Legislature.

- A license sold to “a Chinaman, named Aki” for $71,000 and another individual for “similar consideration.”

- A desire of the missionary group for the Kingdom of Hawa'i to be annexed by the United States.

The first two points are an obvious rhetorical sham much as any modern political advertisement used to attack one's opponent is. The third point is not. Annexation provided a path for activist members of the missionary group to gain security and permanence to their power.note

In a 33-page handwritten history of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Republic presumably authored by William De Witt Alexander, a co-conspirator, found in the Alexander Family Papers at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, a slightly modified explanation was given: "Among the measures urged by the King and opposed by the Reform party were the project of a ten million dollar loan, chiefly for military purposes, the removal of the prohibition of the sale of alcoholic liquor to Hawaiians, which was carried in 1882, the licensing of the sale of opium, the chartering of a lottery company, the licensing of a Kahunas or medecine [sic] men, ie. Systematic efforts were made to turn the constitution question into a race issue, and the party cry was raised of 'Hawaii for Hawaiians.'" Ironically, W.D. Alexander's missionary father, W.P. Alexander, wrote had written thanking William Hooper for sending him poppy flowers, "I have no objections to cultivating the poppy at present, & have planted the seed, hope they will grow and yield opium." (see reel 1, letter dated 23 February 1839 to Wm. Hooper Esq. and reel 3).

Charles Reed Bishop, who unlike his dear friend William Little Lee--who had died of tuberculosis in 1857--actively supported annexation, presented a more forthright resolution to the leading agitators of the group saying the “King has encroached on our rights…it means either a new constitution, or one with material reforms, which I am sure we shall have.” Dole readily admits that they were a minority opposition, but this did not matter.

What neither Dole nor Bishop admit was that they were also emboldened by the fact that Claus Spreckels had left for San Francisco after Kalakaua had become fed up with his financial manipulation of the government. Kalakaua bought off Spreckels with a loan from the British. The missionary group, which ironically called itself the Hawaiian League, armed themselves and successfully sought out the support a large contingent of a local militia group numbering less than 200 men, the Honolulu Rifles, and their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Volney V. Ashford (Ashford would later regret his involvement after realizing that the missionary group was more corrupt than the monarchy; Alfred Wellington Carter, the nephew of Henry A.P. Carter, partner of the Big Five firm, C. Brewer & Co, was also an officer in the Honolulu Rifles). They were ready to use force if necessary, but first approached Kalakaua to see if he would submit peacefully.

Members of the missionary group were tense enough to reveal the lengths they would go to carry out their “Bayonet Revolution” as this event has come to be known. While the League was drawing up a new constitution, one of their members who were on guard duty warned the others that the government was amassing an armed force to attack the Honolulu Rifles's headquarters at the Ali’iolani Hale (the main government building where the Legislature met), according to Dole:

The meeting immediately adjourned, and the members returned to their homes, armed themselves, and started for the [Ali’iolani Hale], to assist in repelling the expected attack. Before reaching their destination, however, they were met with the information that the story of the impending hostile movement was a false alarm.

The League demanded Kalakaua fire Prime Minister Gibson and his Cabinet, accept a group of League members, including William Lowthian Green, in choosing replacement ministers, and support a new constitution. Kalakaua agreed to all. Gibson and the Cabinet were removed and replaced with League members including Thurston as Interior Minister, Green as Finance Minister and Volney V. Ashford's brother, Clarence W. Ashford, as Attorney General.

The Bayonet Constitution fundamentally changed the role of the monarch more than any time since the constitutional monarchy had been created. Article 41 of the constitution states the Cabinet (Ministers of Interior, Foreign Affairs, Finance and Attorney General) would be appointed by the King, but his choices required the approval of a majority of the Legislature, and "No act of the King shall have any effect unless it be countersigned by a member of the Cabinet..." Other provisions were more specific: “the Legislature [Nobles and Representatives], and when not in session, the Cabinet,” and the "whole Privy Council" had to agree with the King on the levying of any subsidies, duties, or taxes (Article 15); the King had to obtain the Legislature's agreement to proclamations of war (Article 26); the Cabinet had to agree to any pardons the King proposed; and the Legislature could now override the King's veto with a two-thirds vote (Article 49).

This was more than the penultimate political attack on the monarchy of the Hawaiian Kingdom, for it was truly a political revolution. Article 59 restricted the vote for Nobles, which were formerly appointed by the King, out of reach for most Native Hawaiians with a new requirement to "own and be possessed, in his own right, of taxable property in this country of the value of not less than three thousand dollars (equivalent to about $74,000* in 2011; only 4,695 people owned real estate in the Islands as late as 1890 and very few of these were Native Hawaiians) over and above all encumbrances, or shall have actually received an income of not less than six hundred dollars (about $14,787.50 in 2011) during the year next preceding his registration of such election." The Chinese and Japanese were not permitted to vote so by pushing the financial requirements beyond the reach of most Native Hawaiians, the minority missionary group was clearly trying to engineer a path for permanent political domination of the Legislature and, consequently, the Cabinet through the Bayonet Constitution.note

These are rough comparisons based on the Consumer Price Index. Obviously the property values are exponentially higher today than they were back then. What we really need to know is that these figures were specifically devised to limit the vote of Nobles to relatively well-off haoles.

Even with the Constitution rigged in their favor, though, the missionary group still were not sure they could control the Legislature so they attempted "to balance the vote with the Portuguese vote," according to Chief Justice Albert Francis Judd--Portuguese plantation workers, which outnumbered other white voters, would, it was believed, vote according to their overseers whims.

It is difficult to understand why Kalakaua capitulated seemingly so easily to the Hawaiian League had we not become aware from later events how tenuous the King's security really was. Kalakaua's sister wrote:

He had discovered traitors among his most trusted friends, and knew not in whom he could trust; and because he had every assurance, short of actual demonstration, that the conspirators were ripe for revolution, and had taken measures to have him assassinated if he refused. His movements of late had been watched, and his steps logged, as though he had been a fugitive from justice. Whenever he attempted to go out in the evening, either to call at the hotel, or visit any one of his friends' houses, he was conscious of enemies who were following stealthily on his track.

In 1890, the McKinley Tariff was introduced and passed in the Republican-controlled US Congress. Overall it was protectionist, raising tariffs to 48.4 percent ad valorem on average. Sugar was dealt with in a more complicated manner. It actually removed all duties on raw sugar coming into the US, while ending duty-free status to countries who imposed unequal or unreasonable duties on US products. However, it placed a bounty of two cents a pound on American-grown sugar. This caused a financial panic in Hawai'i where the economy was reliant on sugar exports to the US. It also provide impetus for both the missionary group and sugar plantation concerns, which were often intricately connected, to renew a push for annexation to the US--Gerrit Parmele Judd's last undone triumph. The only significant political obstacle was the Native Hawaiian monarch. While the monarchs had nearly always bent to the will of their missionary teachers and haole advisors, this was one issue they consistently resisted.

In 1891, Kalakaua fell ill and went to San Francisco on the advice of his doctor, but died there at the Palace Hotel. His sister, Lili'uokalani succeeded him. Meanwhile, it had become increasingly clear that the missionary group had miscalculated in designing the Bayonet Constitution. In 1890, enough haole electors defected from voting for the missionary group's slate of Nobles that the Legislature voted out the Cabinet put in place by the Bayonet Revolution. After the 1892 election, the Cabinet was constantly changing as the missionary group in the Legislature tried to form alliances but only one Cabinet they supported was put in place and this did not last long. Both these legislatures petitioned for a new constitution to replace the Bayonet Constitution. On Saturday, January 14, 1893, Queen Lili'uokalani was prepared to proclaim a new constitution, which included provisions naming her heirs, returning absolute veto and power to appoint the nobles (limited in number to 24 while the representatives were to increase to 48) to the monarch, and prohibiting foreigners from voting. Just before doing so, she met with her all-haole Cabinet who refused to sign it. Consequently she told a gathering at 'Iolani Palace assembled for celebrations to mark the end of a legislative session that a new constitution would have to come at a later time due to the lack of support from the Cabinet.

At the time of the denouement of events between Queen Lili'uokalani and the missionary group, the American military cruiser, USS Boston, was at the port of Honolulu having just returned from a trip to the island of Hawai'i, with a force of "blue jackets" (sailors) and marines, and United States Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary John Leavitt Stevens onboard. The missionary group formed a "Citizen's Committee of Safety" (with obvious reference to the French Revolution and American Revolutionary War groups of the same name) and made an agreement with Minister Stevens. Under the pretext of protecting American lives and property, a force from the Boston would be landed, and if the Committee occupied the Ali’iolani Hale and proclaimed a new government, he would recognize it.

Minister John L. Stevens |

Queen Lili'uokalani had provided a window of opportunity and the missionary group held at least four meetings between Saturday afternoon and Monday evening to shepherd events along after Minister Stevens had returned with the Boston. The first, where the Committee of Safety was appointed, was held at William Owen Smith's house; a second meeting was held at William Richards Castle's house on Sunday morning; the third was held at Lorrin Thurston's office on Monday morning; and the fourth was held on Monday evening at Henry Waterman's house.

The play began to unfold sometime after 3pm on Monday, January 16 when the Committee of Safety delivered an appeal to Minister Stevens requesting protection for American lives and property. The problem with the credibility of the request was that only five of the letter's signers were Americans: Henry Ernest Cooper, John Emmeluth, Theordore F. Lansing, John A. McCandless and Frederick W. McChesney. The four who organized meetings and a fifth, William C. Wilder, brother of Samuel Gardner Wilder, were all members of missionary group and Hawaiian subjects. There were also two German nationals (Crister Bolte and Edward Suhr) and a Scottish national (Andrew Brown).

Around 4pm, the American force of 180 servicemen from the USS Boston landed with artillery and small arms, and instead of moving to protect Americans, they marched up Front Street, dropped off a few men at the U.S. Consulate office, and split into two groups a little further down Front as one group went down Merchant Street and the other down King Street with both heading parallel to each other as they headed towards the Ali’iolani Hale where they held a position between that building and armed forces of the Hawaiian Kingdom located a few hundred yards to the north, nearby barracks, and a station house about a third of a mile away.

Later that evening, Honolulu Police Deputy Marshal Arthur Brown and Captain Robert Parker Waipa arrested Queen Lili'uokalani for treason at her private residence, Washington Place. Most of the Queen's guard had gone home for the evening, and she was taken to 'Iolani Palace* where she was handed over to Honolulu Rifles Captain Joseph Henry Fisher (Fisher, a teller at Bishop & Co), presumably on Chief Justice

Albert Frances Judd's instructions though he denied knowing about the unfolding events until the next evening.note

It’s not clear where the Hawaiian Kingdom’s forces had gone.

As she was being led away from her home, Lili'uokalani saw the Chief Justice enter her home. She later learned that he had a warrant and seized all "the papers in my desk, or in my safe, my diaries, the petitions I had received from the people,--all the things of that nature which could be found were swept into a bag, and carried off by the chief justice in person." These papers were taken to the Honolulu Fort where he put them under lock and key. Lili'uokalani's papers were kept from her by the Judd family for the entirety of her life. Several years after she died, they were finally released for inspection in 1924.

Although the Queen and her Cabinet had sent a note to Minister Stevens on Monday along with a copy of a public notice providing "assurance that any changes desired in the fundamental law of the land will be sought only by methods provided in the constitution itself," and reiterated the same on the 17th.

Stevens colluded with the missionary group. At 1pm on Tuesday, the 17th, two Cabinet officials, Interior Minister John F. Colburn and Attorney General Arthur P. Peterson, met with Minister Stevens and were told by him that if the Queen's forces attacked the insurrectionists, the American servicemen would intervene.

At 2:30pm, members of the Committee of Safety and Sanford Dole went to the Ali’iolani Hale and proclaimed a Provisional Government. Sanford Dole was named President, James A. King would be Interior Minister, Peter Cushman Jones the new Finance Minister, and William Owen Smith the Attorney General (Francis M. Hatch was named Foreign Minister several months later). As they were concluding their proclamation, 50 Honolulu Rifles associated with the missionary group arrived to protect the Committee members. The Honolulu Rifles were supplemented in the Revolution by the drei hundert, or 300, an armed German-national force of some 80 individuals.

Although there is some debate about the exact timing of what happened next, Cleveland's special commissioner who arrived in Hawai'i before the end of the month to investigate,

believes that Stevens recognized the Provisional Government as early as 3pm. Lili'uokalani's Cabinet sent a request to Minister Stevens asking for his assistance in maintaining peace, explaining that "certain treasonable persons" had occupied the Ali’iolani Hale and "pretending that your excellency, on behalf of the United States of America, has recognized such Provisional Government." Stevens replied that he no longer regarded them as ministers as he now recognized the Provisional Government (he later referred to the Queen and her Cabinet as “a semibarbaric court and palace”).

Subsequent to this, Queen Lili'uokalani and her Cabinet yielded her authority to the Provisional Government in protest explaining that she did so because Minister Stevens had landed the American military force and declared his support for the Provisional Government. She concluded:

Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, under the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

Chief Justice Albert Francis Judd said the revolution was justified because Queen Lili'uokalani's proposed constitution, though it was never proclaimed, “would have made it impossible for white men to live here.” This was an ironic imitation of his father's dictum decades earlier “that the foreigner could never consent to be ruled [by Native Hawaiians].” Although he denied knowledge of the secret activities of the Committee of Safety until after the Provisional Government made its proclamation. Beginning in 1881, Judd would serve as Chief Justice for 19 years.

The Revolution was running on a schedule. President Harrison had been defeated in the election held in November 1892 and Grover Cleveland was to be inaugurated as the new president in March 1893. A few days after the Revolution, the Provisional Government sent William C. Wilder to Washington to request annexation of Hawai'i. Cleveland later observed: "between the initiation of the scheme for a provisional government in Hawaii on the 14th day of January and the submission to the Senate of the treaty of annexation concluded with such government, the entire interval was thirty-two days, fifteen of which were spent by the Hawaiian Commissioners in their Journey to Washington." On March 11, Cleveland appointed James H. Blount to investigate what occurred in Hawai'i in January (the events above are based largely on his report though supplemented by other sources). Blount delivered his report in July and before the year was out, Cleveland informed Congress of his desire to withdraw the treaty for annexation from the Senate, citing his belief that "Hawaii was taken possession of by the United States forces without the consent or wish of the government of the islands, or of anybody else so far as shown, except the United States Minister [Stevens]." Cleveland demanded Dole and the provisional Government return Queen Lili'uoklani to her throne, but did so without invoking the threat of force, so Dole boldly refused, reminding the US President that he had no authority over Hawai'i.

The sentiment of Reverend Sereno E. Bishop (a son of ABCFM parents and a missionary himself) wrote in published letter to Blount, ruled the day as the missionary group was finally able to complete its project:

As intimated in the Star such a weak and wasted people prove by their failure to save themselves from progressive extinction, and their incapacity to help or defend the denizens of Hawaii, their consequent lack of claim to continued sovereignty. Their only claim can be to the compassionate help and protection of their neighbors. It is not an absurdity for the aborigines, who under most favorable conditions have dwindled to having less than one third (now barely one fourth, probably) of the whole number of males in the Islands, and who are mentally and physically incapable of supporting, directing, or defending a government, nevertheless to claim sovereign rights? It would seem that the forty millions of property interests held by foreigners must be delivered from native misrule. Not to do that will be wrong!

In lobbying the Senate, Samuel Northrup Castle had earlier argued why the Native Hawaiians owed annexation to the US:

Citizens of the United States have spent millions of money as well as years of weary labor in Christianizing and civilizing the people; in giving them a written language, and books,, and schools, and churches, and laws, as well as a civil polity.

Left unmentioned was that while the missionaries giveth with one hand they taketh away with the other, as another wealthy sugar plantation owner would admit so forthrightly: “No natives have property.”

The Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs held its own investigation in early 1894. The Committee was chaired by John Tyler Morgan, an Alabama Democrat, a Confederate General who favored segregation and was a known imperialist who later supported the US takeover of the Panama Canal, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. The investigation was really nothing of the sort. The record clearly demonstrates the “investigation” was aimed at providing an opportunity for the missionary group and its allies to rebut Blount's report as well as to show favorable reasons for annexation of Hawai'i.

The following taken from a statement and testimony of William Brewster Oleson, a teacher at the Kamehameha Manual-Labor School of Honolulu (forerunner of the Kamehameha Schools), provides a telling sample of both the ethos and inconsistencies of logic portrayed by the revolutionaries' testimony:

I have been a consistent supporter of the Hawaiian monarchy, in public and in private, out of deference to the prejudices of the aborigines…

The foreign population that had been united in 1887 in the movement for a new constitution had lost its cohesion through the operation of several causes. Notably among these was the anti-Chinese agitation, which enlisted the mechanics and tradesmen against the planters and their sympathizers. So long as the foreigners were united they were able to guide the legislation and administration of the Government. When they became divided the leaders of the anti-Chinese agitation joined forces with the natives, and the political leadership fell into the hands of men who had little sympathy with the reform movement of 1887. I wish to state here that when I say foreigners I mean voters in the Hawaiian Islands of foreign extraction, and when I say natives I do not intend to raise any race question, but simply to show that the majority in Honolulu were natives.

The events of Saturday, January 14, convinced me that there was no option left to the intelligent and responsible portion of the community but to complete the overthrow initiated by the monarch herself. It was essentially either a return to semibarbarism or the continued control of the country by the forces of progress and civilization, and few men hesitated in making the choice, and the development of events has confirmed their decision.

Morgan dominated questioning of the witnesses and many of his questions were leading, though none of the other committee members asked critical questions either. There were numerous affidavits admitted into the record which were mere unchallengeable statements given by the revolutionaries and their supporters. Two public notaries witnessed the affidavits entered in the record, and one of these notaries was Alfred

Wellington Carter, a Punahou alum and officer in the Honolulu Rifles.

In response to President Cleveland's opposition to annexation, the Provisional Government opted for a more permanent solution and formed the Republic of Hawai'i on July 5, 1894 (Thurston and Dole had initiated, separately, the first draft of the Republic's constitution). Dole remained President and King stayed on as Interior Minister as did Hatch as Foreign Minister, but Samuel Mills Damon became Finance Minister. (In 1894, Damon also bought out Bishop's shares in Bishop & Co. and Bishop moved to San Francisco, for unknown reasons, where he lived out his life). Henry Cooper served as Foreign Minister for a period then Attorney General. Consequently all the Cabinet officials in the Provisional Government and Republic were from the missionary group, except for Henry Cooper, who served in several positions over the next several years. While the non-missionary group signers of the Committee of Safety's request to Minister Stevens were kept on for a while as “advisors” to the

Provisional Government, they held no other official office of importance.

Colonel Zephaniah Swift Spalding, a veteran of the Civil War, former US consul to Hawaii in the late 1860s, and a wealthy sugar plantation owner had explained how the new government, which he had helped to overthrow the old by financing the “sinews of war,” functioned:

We have now as near an approach to autocratic government as anywhere. We have a council of fifteen, perhaps, composed of the business men of Honolulu some of them working men, some capitalists, but they are all business men of Honolulu. They go up to the palace, which is now the official home of the cabinet they go up there perhaps every day and hold a session of an hour to examine into the business of the country, just the same as is done in a large factory or on a farm.

They control [the government]. They assemble--“now it is desired to do so and so; what do you think about it?” They will appoint a committee, if they think it necessary, or they will appoint some one to do something, just as though the Legislature had passed the law to be carried out by the officers of the people.

Annexation finally came after Cleveland's successor, William McKinley, took office. McKinley, whose administration followed the most colonial policy in American history, became president in 1897. The President of Hawai'i, Sanford Dole, surrendered sovereignty of Hawai'i to the United States on August 12, 1898 and the Islands became a US Territory.