Similar to religions everywhere, the most widely practiced religion in Myanmar, Buddhism, is not always

practiced in its truest form. It is practiced with elements of Hinduism and commercialism and alongside

pre-Buddhist/Hindu Nat worship. Water is ritualistically poured over Buddha statues and old banyan trees

at famous pagoda complexes. A statue of Buddha bathed in colorful, electric lights is said to be more

powerful because of the lights. The faithful pray in front of a Buddha statue before moving on to a room

with Nat statues where they pray also. A guide criticizes a couple he sees praying together, “People are

not supposed to go and meditate with their husband or wife. They are supposed to clear their minds and

remove themselves from this world when they meditate. How can you meditate with your wife?” Aside from

these imperfections in the way a religion or philosophy, as many adherents to Buddhism I have met maintain

it is, there are institutionalized practices which usually remain the same even outside of sects or the two

main branches of Buddhism, Mahayana and Hinayana.

Just about every rule I had thought a monk lived by, I saw broken in Myanmar: monks walking with girls, taking

pictures while laughing with women at a pagoda, wearing sunglasses, accepting and paying for things with money,

and walking as if they were strutting down the road with part of their robes thrown over their heads. Not the

sort of devout behavior I would expect of a monk and the kind of behavior I never saw reflected in the actions

of the country’s seemingly more devout nuns. I came to think it would be just a matter of time before I might

see a Burmese monk drinking alcohol or entering a brothel. When I went to a bar for a couple of beers, I did

see a young bald man sporting a moustache, watch and layman’s clothes in a bar. Could this be a monk in

disguise, I thought. After all I had seen a monk with a goatee while traveling through Myanmar. It may

just been that the Myanmar Beer I was drinking was playing with my imagination,… or was it?

The people I inquired about such things I had seen said that these were either not real monks, that Buddhism is at

a low point in Myanmar, or more pointedly, blamed the government for co-opting the Buddhist leadership in the

country with expensive gifts.

It can be seen everywhere that Buddhism has traditionally been an important part of the life of people throughout

Myanmar through the magnificent pagodas that dot the landscape. In fact it is remarkable that huts will surround

the one permanent structure in an area, a pagoda made of bricks, stone or some other permanent.

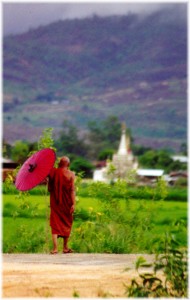

Buddhist monk

Yangon is a sprawling city bustling with activity. In the older center of the city, extending from the golden

Sule Pagoda, people sell food and drinks, betel nut, cheroots and cigarettes from small, roadside stands. Unlike

some cities where people merely walk from their cars to the entrance to buildings, Yangon is characterized by

throngs of people walking to and fro. Crowds gather outside a movie theater or sit at small, plastic chairs

on a sidewalk sipping tea and eating a snack. People selling food and various household goods line the sidewalk

making it all but impossible to walk by. The city bird is the crow. Their screeches become more noticeable when

the din of the traffic and the chatter of the masses lessened by a brief rain shower. The rain is the only relief

from the air thickened by the black smoke belching from over used cars. Blackish gray stains from the heavy rainfall

and extremely humid air mar the city’s common, older buildings just as in all of Southeast Asia’s cities.

Yangon's old city center

Mandalay is the least industrialized, least commercialized, least developed world reknowned city I have ever visited.

Neighborhoods filled with huts buffer the city at the edge of the Ayeyarwady River. Mandalay in May is dirty.

There is dirt on the side of the road, and at times, in the middle of the road. When trucks drive by, the dirt gets

blown into the air. When the winds kick up, which is common, they also blow the dirt around. In the outdoor, central

market area, the rains turn the dirt to mud and the numerous carts, cars, trucks and pedestrian traffic turns the mud

to slush.

Then contrast between this setting and the women and girls at market with their faces decoratively covered with

thanaka paste* and hair adorned with beautiful, fragrant flowers (*made from the rubbing of bark of the tree

against a whetstone, thanaka helps keep the skin cool in the heat).

Throughout Myanmar, I found that electricity was available, but unreliable. In Mandalay, I was told that because

the river (the Ayeyarwady River) was low, that electricity was being rationed. Electricity would run for eight hours,

then be cut for eight hours, then run again for eight, and so on. The sun would fall at six in the evening, and the

air around the streets becomes filled with chatter of people enjoying the relative cool, horns of cars honking to get

slower trucks, cars, scooters, bicycles and pedestrians out of the way, and the sound of generators where people are

fortunate enough to have one. Walking down the crowded street, it would be difficult to find your way and avoid rain

puddles were it not for oncoming traffic lights, alternating constantly between circular beams to coronas of light

surrounding silhouettes between their source and you.

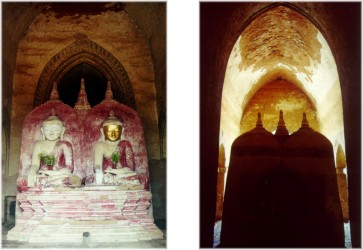

view of Gawdawpalin Pahto (white pagoda

in background), built in

the thirteenth century, and rebuilt after an earthquake in 1975.

With some notable exceptions, the beauty of Myanmar lays not in its decrepit cities or smaller towns, but in its

villages and the general populace. This holds true especially in Bagan, which at the same time is also the exception

to the rule. Bagan is fascinatingly beautiful because of its centuries old pagodas, their architectural forms, Buddha

statues and paintings as well as its outlying countryside where traditional life can still be seen, smelled and tasted.

Jaggery is a caramelized candy from the juice of the palm. Sometimes it is made plain or mixed with some coconut, or

perhaps some milk. Toddy, or a palm beer, is made from the palm juice as well. It is sweet like wine when it is

first made, but becomes more bitter as if ferments throughout the day. You could see ladders attached to the sides

of palm trees everywhere in the Bagan countryside and so I realized that jaggery and toddy were surely popular. I

even asked a few people if they drank toddy and how old they were when they first drank it. My waiter at a restaurant,

now a young father of a ten year old and a five year old, told me he first drank toddy when he was ten. Then he

offered to buy me one, but it was much stronger than the toddy I had tried the day before. Mumu is a fifteen-year

old girl, she first drank toddy when she was five, and her friend, Kindidasu, first drank the brew when she was six.

Water is a like gold in many places throughout Myanmar. In the countryside of Bagan, I saw a bullock cart with a

wooden barrel on it as I saw many places. I asked the woman of the household about it and she explained that they

it took them about three hours to get water for their everyday needs. I saw a group of people waiting with large

cans at a cement stoop of some kind. When I got closer I saw water dribbling out from the bottom. This is where

the villagers would get their water. In Nyaung Shwe, I saw a young woman carrying two pails hung from a bamboo

pull she carried over her shoulder make several trips to a well and then back to her home. She would be gone for

about five minutes before she would reappear with the empty pails. She made at least four trips before she returned

having washed and changed her clothes, to pick up the last two pails of water. I also watched a child as he rode his

small, toy car across the street with two plastic containers to and from another well to get water for his own

household.

Bagan, the historical site, is a truly remarkable outdoor museum. The location of pagodas built from as early as the

ninth century and as late as the fourteenth century, though construction continues on smaller pagodas in the plain today,

Bagan is easily as impressive as Angkor in Cambodia.

One of the villagers reigns over Nan paya, a Hindu structure made of brick dating from the eleventh century. He

keeps the opening locked and does not permit visitors to take pictures because he sells his own pictures of

the temple, so my informal guide, a fifteen year old girl tells me after she rejoins me when I leave the temple.

The temple, like many of the historical pagodas in Bagan, actually houses a smaller walled structure within it.

The temple has several beautiful carvings of the four-faced Brahma, which are only visible with the aid of a light

provided by the caretaker.

|

| Dhammayangyi |

Gawdawpalin pahto (thirteenth century) is a majestic pagoda though Ananda pahto (twelfth century) is superior in its

architectural beauty. Both have spectacular Buddha images, and Mingalazedi (thirteenth century) near Nan paya also has

beautiful paintings. I had visited these and a handful of other pagodas in Bagan when my guide had suggested I see

Dhammayangyi (twelfth cetury) and Sulamani (twelfth century) before I leave Bagan. You could easily spend weeks in Bagan,

slowly, meticulously exploring the ruins, but I only had a few brief days and these two pagodas were, for me, the most

spectacular I have ever seen. The combination of Buddha statue styles and paintings were well preserved and beautiful.

I only wished that I had an expert to guide me through the significance of the intricate stories painted on the walls

of Sulamani and to share what is known about specific statues at Dhammayangyi. I feel fortunate that I have seen such

marvels before they have been obscured by glare behind high security glass cases.