One man in Shan State who approached me in desperation for help to get a letter to an acquaintance in America

told me that he earned 200 kyat per day and paid 3500 kyat in rent per month. So I calculated this left him about

2500 kyat for food and other expenses per month. Another man in Yangon told me how he had convinced his son who is

employed by the government as a mine engineer at 6000 kyat per month to come back to Yangon and work as a driver for

DHL where he can earn 20,000 kyat per month.

At 6000 kyat per month, a town or city dweller can purchase a water buffalo for plowing fields, which may cost about

40,000 kyat, after seven months of saving his money for nothing else. A farmer would have to save for much longer.

A strong bullock, used for pulling carts may cost 70,000-80,000 kyat while a weaker bullock may cost 45,000-50,000 kyat. A wood cart may cost 25,000 kyat.

So to put these prices in perspective using my admittedly unscientific base salary of 200 kyat per day, a strong

bullock may cost the equivalent of a nice pair of Nike running shoes, but in a country where the salary for city

workers who make much more than the farmers who would need a bullock in the first place, is about $3.00 per day.

So it would take about two days of work for the average city worker to earn the $6.00 per minute price of a phone

call to America, or a little more than two hours to earn enough money to buy a Myanmar made soda pop at 70-80 kyat

(forget an imported Thai Coca Cola at 300-350 kyat). It will take nearly two years to save for a 45,000 kyat, new

Chinese, Pheasant Sport, bicycle while living at home where rent and food are taken care of by your parents. My

bike in America costs about 15 times as much, but gets much less than 1/15th use the Chinese bicycle will get.

Those who own motor vehicles can purchase two gallons of petrol at the official, government price of 180 kyat

per day*. On the black market the cost is 800-900 kyat. Its no wonder then, why thirty people may sit inside,

on the roof, and hang on the back of one of the used Toyota Hilux workhorses for a ride from town to town rather

than spend 4000-2000 for a taxi ride that only foreigners seem to take. Nor is it then a wonder that a meal

consisting of a plate full of rice and tofu crackers, chili sauce, a lettuce, onion and tomato salad, a bean

sprout and tofu soup, fried tofu curry, boiled rice and tea with condensed milk and sugar costs a meager 500 kyat.

[*Note: Three gallons could be purchased per day before the border fighting with Thailand due to yaba, or

crazy medicine (amphetamines) being smuggled into Thialand from Myanmar. Now (May, 2001) goods have stopped

coming into Myanmar from Thailand and prices are escalating. When I arrived in Yangon, I received 630 kyat

for one US dollar. Two weeks later the government had arrested moneychangers, whose profession is officially

illegal, but who are allowed to stay in business unofficially, in Yangon because they were changing 800-900 kyat

to the dollar.]

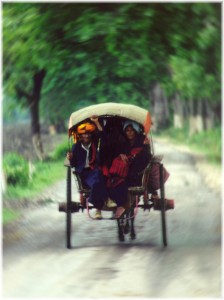

Horsecart, Nyaung Shwe

Sharing borders with one of the most economically successful countries in Southeast Asia, Thailand, Myanmar is

impoverished. It’s ironic that this poverty, in some ways at least, has led to the beauty of Myanmar. Would the

longyi still exist if wealth and all its entrapments were knocking on Myanmar’s door? Would people still place

sprigs of leaves on their cars and trucks to adorn them? Would women, and sometimes men, still decoratively apply

thanaka on their faces? Would women still wear fragrant flowers as bracelets around their wrists or adorn their

hair with beautiful and fragrant flowers?

Poverty loses its beauty when, behind the smiles of the people who know no better life, you see dignity lost.

It’s the rainy season and yet I was foolish enough to leave my hotel without my umbrella. After walking about

two blocks, the rain began to come down heavily. I ran across the street and joined a growing crowd of people

who had congregated under the awning of an upscale building. Those in charge of the lobby were quite disconcerted

over having such a mob in front of their store so they decided it was time to clean the covered portion that did

not extend onto the sidewalk. It was a clear message that the management wanted to keep the riffraff out from in

front of their store.

Along the way to Bagan, our boat stopped to let off passengers at a sandy beach, which raised into a small hill of

sand where nothing visible could be seen beyond it. There were numerous people waiting for the boat to arrive and

several women with fruit, drinks and prepared food to sell the passengers. The boat hadn’t anchored, but it was

moving closer to the beach. I was standing up at the side of the boat looking at the scene on the beach when one

of the women selling food spotted me and was motioning for me to buy something from her. She held up different

items and I shook my head to one item after another. Then she held up a bag of samusas and I tried to ask how much

they were. Her response was to heave the bag to me and then try to signify one-hundred kyat with her hands. I was

going to throw the 100 kyat note back to her, though I realized it would never make the distance because it was too

light, and she signaled for me to wait until the boat got closer. The boat did anchor for a few moments near the

shore, but the plank which was pushed out to let passengers walk to the beach kept the gulf between the beach and

the boat fairly long. I scrunched up the bill a bit and threw it, but the slight breeze took it and it fell in the

water about half way between the boat and shore. Still holding her flat basket of food, she jumped in to the water,

and wadding chest in the river, she retrieved the bill. By the time she got back to shore, others were conducting

similar transactions and the money was never reaching the shore. It was a spectacle, seeing people jump into the

water, and it sadly seemed to me that these poor villagers were losing a bit of dignity in the process of surviving.

It wasn’t long after this snack of tasty, but greasy samusas and a small meal onboard the boat that I started to feel

like something was wrong. I suddenly felt dizzy, queasy and the sounds all around me became extremely irritating.

Then, I felt a tremendous desire to throw-up. I got up and prayed (figuratively – I’m not very pious) that I might

make it to the bathroom before I hurled. I was about three feet from the door of the bathroom when I launched a

small mouthful of my stomach’s contents that I just couldn’t keep contained. Then I made it to the bathroom and

hurled until my stomach had to be empty. It didn’t take long before my body was expelling everything it could as

if a flood from the other end. [I have omitted a real life advertisement for Imodium that I would otherwise have

placed here until their company agrees to offer me some compensation].

Beggars can be seen in any country, but they are a relative species. The destitution of a beggar in San Francisco

can in no ways be compared with the beggar in Bangkok or those who I saw in Myanmar who were missing limbs or had

large open sores where flies fed hungrily. Children beggars are more complicated. Often times they beg because

their parents make them. Other times, they beg for themselves. I’m newly arrived in Myanmar, I don’t have my

bearings set yet, and a child comes up to me with outstretched hand asking for money. I give her 20 kyat to leave

me alone. This satisfies the child and she leaves. Three cents.

I was asked by school children for a “stylo”, or pen from the old stylograph, several times while traveling through

Myanmar. I told one person that I was surprised by this and he casually said, “Oh, they will just sell them,” but

several others I spoke with said that school children really need pens. At a pagoda complex, one girl came up to

me wrapping a small bracelet made of sweet smelling star flowers around my wrist. I say “No” and she tells me, “This

for you. No money.” Then she asked me for a stylo. On a large passenger boat, a boy who I had seen several times,

asked me for a stylo when nobody else was around. In Bagan, school-aged children also asked me for stylo.

Education seems to be at a low point in Myanmar. After making some innocuous comment about the internet, one student

told me that he was not an expert. “We are lucky if we can just touch the keyboard of a computer,” no matter actually

learning how to work a program. He wants to study engineering, but the government has chosen Geography as his area of

study for him. When nearly no one can leave the country without filling out piles of paperwork and handing out large

quantities of “gifts”. His co-worker was a university student until his school was closed. Since the student

demonstrations were ruthlessly put down in 1988, few universities have been permitted to stay open or reopen. A

pen may be a valuable commodity for a young student in Myanmar, but when higher education isn’t even available to

those who would otherwise have the means to gain it, a visitor to this country can only wonder how difficult it will

be to improve the economic situation with no future skilled workforce.

An uneducated populace is a cheap form of labor. I saw a crew of four people, women and men, cleaning reflector

bumps on the road that surrounds Mandalay Fort. One person had a bucket of water to wet the bumps while the others

scrubbed the bumps clean with a stiff brush and toweled them dry.

The conveniences you would expect to be available in any international city were not available in Mandalay, the last

capital of Myanmar before the British finished their subjugation of the country in the late 1800s. A block away from

the walls of the old fortress, known as Mandalay Fort, people can be seen in mid-day bathing at the street corners

where the wells are located.

Since the unofficial exchange rate is so high, foreigners are extremely rich compared to the population of Myanmar.

Getting a foreigner to hire your service is a dream for many, so a white man like myself walking down the street will

be accosted a half a dozen times with the words “Where you go?” as an opening line to the ultimate question,

”What can I do for you? “

Passing by a village near Nyaung Shwe, I asked some of the villagers who were just returning if it was all right

for me to enter it with my camera. They motioned that it was okay and so I began walking around the village taking

in the sites of the different life than I was accustomed to that went on there. Small canals ran through the village

of wood huts on stilts with a few boats being rowed around. A woman approached me and signaled that she would row me

around for two hours for two-hundred kyat (about 30 cents). There didn’t seem to be anywhere she could take me by

boat that I couldn’t walk, but for the price I figured I couldn’t lose so I agreed. She jumped up for joy and then

started to run about aimlessly in the excitement looking for an oar. I almost tipped the boat over while getting on

and every time we went under a small foot bridges made of bamboo, I had to duck deep so I wouldn’t get hit, but it

was an interesting trip if only because the vantage point from the boat was unusual. Later I asked someone where

the bamboo for the bridges and stair leading into huts came from because I didn’t see any bamboo trees at this

elevation, and learned that the bamboo came from the surrounding mountains. We passed a couple of boats with a

man holding two sticks out into the marshy water with small, hard metal nets at the end and wires connecting the

sticks to small batteries in the boat. At first I couldn’t understand why they might be looking for metal objects

in the canals, then, after seeing dead fish in another boat, I realized they were fishing by electrocution. My

boat guide didn’t speak a word of English and several times rowed me into a dead end. Two of her small children,

one only wearing a shirt and underwear, followed us from the side of the canal. The mother would tell them to wait

or go back home and they would start to cry so after a while of them following us, she let them get on the boat. I

found out that she had four small children and she showed me her hut as we floated by. The tour took not two hours,

but one stretched out hour and then a man got into the boat and told me it was over. I made sure she understood that

she didn’t keep to the agreement that she was to take me out for two hours, but then handed her the two-hundred kyat

all the same.