For all the news that the town generates, the impression I left with after my brief visit was that Johor Bahru is a pretty unexceptional town. The highlight of my experiences had to be the Royal Abu Bakar Museum and

my introduction to the Indian eateries of Malaysia. The museum is the Sultan of Johor's historic residence. Portions of it have been converted into a museum which visitors can wander through. The house was beautiful, and

still maintained an aristocratic air while giving a much more livable appearance than the palaces of Europe built a couple of centuries earlier. However I wander if this can apply to the Sultan Abu Bakar of a century ago

who was, afterall, a Malay living in a European style house. Two of the collections found at the museum are a kris collection and a trophy collection. The kris collection is absolutely spectacular and a must see

for anyone slightly interested in the object. The trophy collection belong to one particular sultan who was an avid hunter. The objects in the collection speak for themselves: elephant feet trash cans, ashtrays, and a decanter holder; a

tiger skull fitted with silver for serving a smoker's dish; and other slightly less exotic pieces.

Muslim Indian merchants, along with Arab merchants, had an obvious impact

on the religion that dominates in Indonesia, the Southern Philippines and

Malaysia. My greatest appreciation of the Indian people in Malaysia was

through their food. Fortunately, I was eased into the relationship with

Malaysian Indian food by my guidebook, though I have to say that Karen's

advice to "always observe what everyone else does," helped significantly.

It was about 3:00 in the afternoon. I woke up after a short nap. In search

of food, I decided to explore a small Indian restaurant I came across.

A couple of the Indian men who worked at the restaurant helped me order.

Then one of them served me a cup of rice on a square-cut banana leave and

couple of small dishes of food. The custom, in this and many Malaysian

restaurants, is to eat with your right hand and to keep your left hand

underneath the table (for hygienic reasons where water and a hand traditionally

sufficed instead of toilet paper). Using your hand, you mix your rice and

curry dishes together on the banana leaf. You signal that you have finished

by folding your banana leave in half and wash your hands at a sink in the

corner of the restaurant. Most of the diners at the restaurant ate simply

roti (bread) and curry. After this experience in Johor Bahru, I developed

a routine of searching for an Indian restaurant for breakfast where I would

eat roti and curry (the red curry was my absolute favorite) and drink tea

the local way, with sweet condensed milk.

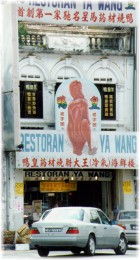

Peking Duck Anyone?

Peking Duck Anyone?

Travel is invariably cheaper in Southeast Asian than in Europe, the

U.S., or even Northeast Asia. If you have a good guidebook or just ask

around, you can usually determine what your options are and they often

vary tremendously. Take the journey from Johor Bahru north to a small town

in the direction of Melaka, called Muar. A taxi would have cost RM150 for

a foreigner, RM100 for Malaysians, or less if you shared the taxi with

others. A taxi to the bus depot in the northern end of town costs RM5,

but a bus costs 90sen (there are 100 sen in RM1). Now a bus ride from this

depot to Muar costs RM10.

The road from Johor Bahru to Muar was filled with endless plantations.

You could tell that the palm tree groves which lined the road were not

wild because the trees were planted in rows. The experience of driving

through these groves was strange because you instantly realize that these

endless miles of tall palm trees are no different than the rows of corn

you might see in the Midwest or orange trees in Southern California, only

the palm trees are much larger.

|

|

After I arrived in Muar, I decided on staying at a hotel at the outskirts

of town. I hired a taxi. The driver delivered me and my bags then drove

off. A man brimming over with self-confidence was standing a few feet back

from the guest-side of the reception desk appearing to watch over things.

A woman behind the desk greeted me with "Yes, how may I help you, sir?"

While I was responding to her, she looked past me and then said, "I'm sorry

sir, we have no more rooms available." I was suspicious of her answer because

the hotel was not bustling with activity - nor was the town - and she seemed

to be looking past me all the while at her "employer." I knew my taxi had

left and dreaded the long walk in the scorching heat carrying my bags in

search of another hotel. I could only speculate while I was denied a room,

but could not arrive at a fair conclusion.

This hotel happened to be near a golf course and they were both just

feet from the ocean beach. There were small drainage ditches alongside

the road that extended all the way into the center of the city which seemed

to be at least a couple of miles away. No one was on the golf course during

this hottest time of day and only a few grounds keepers could be seen as

I looked around. Suddenly, I heard a noise and looked to see a monitor

lizard run away. It was huge. The length of this reptile must have been

at least four feet from head to tail. I searched him out but couldn't find him.

I think he slipped into the narrow ditch which was half filled with ocean

water at the time. All I could see in the ditches were beautiful, bright

orange dragonflies. Still angry at the fact that I was denied a room, I

tried to console myself with the glee at having seen a monitor lizard for

the first time and decided I would search these reptiles out another time.

Inai & Rambutan, Kota Bharu |

With the help of strangers I passed after entering the

outskirts of the town proper, I found a hotel. My embarrassment from being

soaked with perspiration while I inquired about the room was only ameliorated

a bit by the fact that a young, plump man behind the desk had his fingernails

dyed with inai. I had seen it on several women after I had first

learned about the practice of newly wedded women dying their finger tips

or finger nails with inai (a mixture which includes henna) in Khota

Bharu, but this was the first man I has seen with his fingernails dyed

red. When I asked the woman he was working with about this, she laughed

and the man became slightly embarrassed. |

Sleep that first night in Muar was difficult. The ceiling fan did little

to cool the air. At 3:00 in the morning, I heard someone talking as loud

as they possibly could without actually yelling. I could not hear what

the man was saying, but thought he was at the reception desk about twenty

feet away from the door of my room and I immediately suspected he was Chinese

(suspicion based on personal experience in any event). I finally decided

to ask this person to lower his voice. I got out of bed, opened the door

and walked over to the reception desk. There was no one there. Following

the sound of this human megaphone, my eyes looked down the stairs to a

phone which hung from the wall on the first floor where a black man was

talking on the phone. I was embarrassed at the thoughts I had up to then

and watched unobserved as this man ended his loud international phone call.

Its simple things like a good night's sleep that you sometimes forego when

you save a few dollars by staying in inexpensive hotels and guesthouses.

The place where Muar now sits was two small villages as recently as

1887. Abu Bakar, the Sultan of Johore established the town of Bandar Maharani,

(the official name of Muar). It became populated by Malays dislocated through

famine, strife and a myriad other reasons, Javanese, Bugis, Indians, Chinese

migrant labor to work on pepper and gambir plantations, and Chinese merchants

from Singapore and Johor Bharu. When I visited Muar, it seemed to represent

the character of the places I visited on the coast of Peninsular Malaysia:

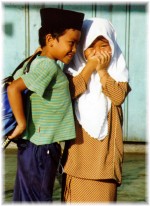

Indian policemen; Malay children dressed in uniforms which include a tudung

for the girls and a kopiah (Muslim cap) for the boys; ethnic Chinese and

Malay run shops. The walkways in front of shops are covered with businesses

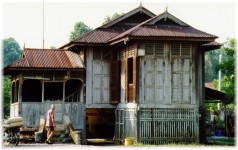

and residences. Sometimes these covered archways begin with arched openings

at a corner of a street. Some have vertical Chinese writing on them. There

was an colorful Hindu Indian temple located on the edge of town and the

Malay residences seemed to predominate outside of the business center of town.

Wandering through the streets, I came across the opening

of a shop where a couple of ethnic Chinese men were crafting wood. Their

shop looked as if it had been operating for more than a century. The hand

tools which hung on the wall near the front of the store added to the rustic

look. I motioned to one of the craftsmen in asking for permission to take

a picture and he approached me smiling. He told me that they were constructing

caskets for Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore whose culture derived from

a certain region in Guangdong (Canton) province. They crafted the caskets

out of solid hardwood with the hand tools I had first noticed. The opposite

ends of the length of the casket are shaped into large, stylized flowers.

It takes them about ten, eight-hour days to construct one casket out of

a solid tree for which they were paid about RM1000 ($400 at the time). |

|

Later in the day, I returned to the golf course area outside of the town

where I had seen a monitor lizard I had since learned was called a biawak.

The area was transformed. The ditches were all but dry leaving behind mud,

crabs, fewer dragonflies than I had previously seen and no trace of the

biawak. It was as if the land had changed hands in a few short hours.

There were people everywhere: on the golf course, jogging on the sidewalks,

couples sitting along the boardwalk, families gathered around a picnic

table, children playing on a swing set.

I was as determined as an amateur zoologist to see the biawak

again. Early one morning, I set out by foot. Walking through the neighborhoods

that extended along the way, a women riding a bicycle in my direction with

a live rooster in her hand, school children riding their bicycles to school

and a few mangy dogs that suffer the heat worse than I do in Southeast

Asia. Suddenly I saw a monkey cross the street some fifty feet before me.

Another one followed then more until over a dozen had crossed the street.

I excitedly followed them until I reached the fence of the home that they

had run to. These monkeys played about on the roof of a home there and

on branches of the trees in the yard. Just after I arrived, they responded

to my presence by scurrying away into a heavy brush-concealed stream that

ran along the edge of the property.

I was as determined as an amateur zoologist to see the biawak

again. Early one morning, I set out by foot. Walking through the neighborhoods

that extended along the way, a women riding a bicycle in my direction with

a live rooster in her hand, school children riding their bicycles to school

and a few mangy dogs that suffer the heat worse than I do in Southeast

Asia. Suddenly I saw a monkey cross the street some fifty feet before me.

Another one followed then more until over a dozen had crossed the street.

I excitedly followed them until I reached the fence of the home that they

had run to. These monkeys played about on the roof of a home there and

on branches of the trees in the yard. Just after I arrived, they responded

to my presence by scurrying away into a heavy brush-concealed stream that

ran along the edge of the property.

This time when I reached the golf course, I was not to be disappointed.

I saw a biawak in the grass beside the walkway and walked closer

to take a picture. He ran across the street and down into the canal where

he swam away. I spotted another biawak next to the canal and he

ran from me as I got closer as well. Then I saw a third biawak much

smaller than the others I had seen and he ran up a tree as I got closer.

He had no where to go as I got closer, but moved around the tree to hide

from view as best he could.

Malacca became great because it was imbued with favorable natural conditions

to make it a great port and because a wandering prince from Sumatra had

the ambition to negotiate its success. Parameswara was a prince from Palembang

when forced to escape to Singapore before the forces of the declining Javanese

Majapahit kingdom destroyed his domain. Parameswara had arrogantly claimed

his independence from the Majapahit. He went first to Singapore where he

was welcomed, but he left several days later after killing the ruler who

had welcomed him. Fearing a repraisal from the Sukothai (perhaps Thailand's

most powerful dynasty), he escaped to a port along the western coast of

Malaysian Peninsula where Muar now rests. He lived here for six years before

his ambition drove him further north to establish a settlement at Malacca

around 1400.

|